Dean Hobart—a Lifelong Love for Outboards

October 3, 2024 - 11:46pm

J. Michael Kelly in Hobart’s C Mod Hydro at Moses Lake, 2024.

Photo by Gleason Racing Photography

By Craig Fjarlie

Dean Hobart has been involved with outboard racing most of his life. Born in Seattle in 1946, he had an early interest in mechanical matters. “I was always best at STEM,” he explains. “That is, science, technology,engineering, and mathematics. My brother was interested in cars. He used to get Hot Rod magazine. There was always an advertisement with Sterling Moss. He had quarter midgets, and we liked them, but they were kind of expensive. When I was nine and my brother was 12, we found an old bed frame in the woods near us. It was made of angle steel. We cut all the rivets apart and used that frame to make our own motor scooter. Sterling Moss things were expensive, so I thought, ‘Well, I’ll just build a hydroplane.’ My grandparents lived down thestreet from Advance Marina. They had an Ed Karelsen kit boat leaning up against the wall; $89.95. I bought that. It was about six inches by 18, in a cardboard box.”

There was more to buy, and it took Hobart a while to earn enough money to finish the boat. “Paper routes,cutting lawns, I saved enough to buy the plywood. The kit was just the frame; you still needed to supply the plywood,” he remembers. When Hobart was about 15 years old, he finished the boat and obtained an engine.“It was a racing style powerhead, but had a long fishing lower unit on it,” he says. “It was a KH-7. Instead of being a Hurricane, they called it a Cruiser. I had to build the transom up a bit to get the cavitation plate level with the bottom of the boat. We drove over to the Sammamish Slough and I’d go up and down from the Kenmore launching ramp to the Bothell bridge and back. I just learned how to drive it.”

Hobart knew if he were to race the boat, he would need a racing engine. “We sold that KH-7 engine and found aKG-4 in a classified newspaper ad. There might be six hydroplanes for sale at a time in those days.” He was ready to start APBA racing in 1962, but first he attended the Pop Tolford novice school, through Seattle Outboard Association. “It lasted three months—January, February, and March. Then they had a novice race. There were enough people for an entire boat race of novices back then, learning how to do this. The first time I ran the KG-4 with the Quicksilver lower unit and a little brass racing prop, I went 45 or 46. That was a big difference. As we started figuring things out, we bought a stainless steel propeller from Mike Jones. My dad and I were talking one time, and I said, ‘You know, these propellers make a difference.’”

At the conclusion of the 1962 season, there was a record race at Lake Lawrence, near Yelm, Washington. A family that previously lived near Hobart had moved to California. “There were two brothers, Fred Miller and Dave Miller. One brother ran A Stock Runabout and the other ran A Stock Hydro. They came up to Lake Lawrence with all their equipment to sell it. The brother with the hydroplane told us it was a Baycraft. We tested it right away and man, it went better.” Hobart bought the boat. “Spent all winter refinishing it,” he says.

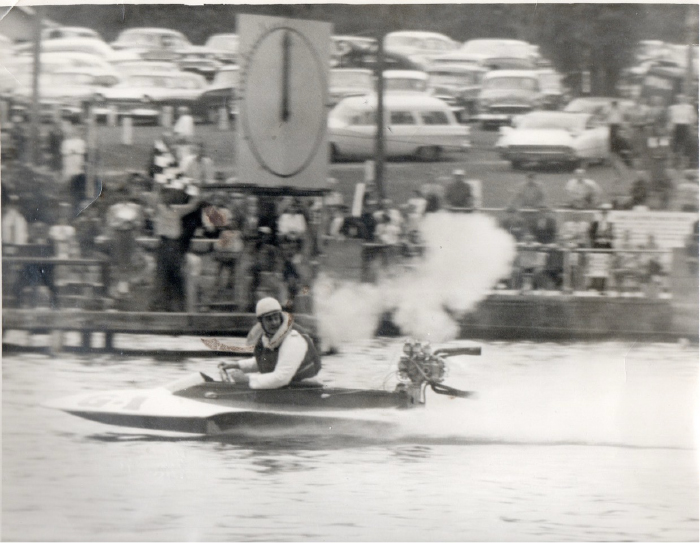

In 1963 there was a spring race at Moses Lake. Hobart tells an interesting story from that weekend.

“Frank Holmes was one of the guys in the Moses Lake Boat Club that put those races on. He owned a sand and gravel company. He was talking to my dad and asked, ‘Is this your A Stock Hydro?’ ‘Yeah.’ He said, ‘My older brother, Butch, ran A Stock Hydro. I still have a few of his propellers in a drawer. Do you want them?’ ‘Yeah.’ He only lived about five minutes from the pits, so he went and brought them back. My dad said, ‘How much do you want for them?’ ‘I don’t know, five bucks apiece, whatever.’ Italian propellers! He sat down and wrote on a piece of paper, ‘If you need to get them worked on, send them to this guy.’ That name was R. Allen Smith, Poppa Smith. I still remember the address: 6329 Thornhill Avenue, Shreveport, Louisiana 71106. I actually had bought a Cary from a guy in New York. It went okay. We didn’t want to work on the ones we got from Frank Holmes yet, so we sent that Cary to Poppa Smith. He banged on it, and it gained four miles an hour. I got third at the Divisionals and finished out the rest of the year. Then, that winter, Jackie Holden was selling his boat. He used to get a new Karelsen every two years or so. It looked a lot like a Sid Craft in those days. He was selling it, so we bought it.”

The number on Hobart’s early boats was 107-R. He applied for a new number in 1964. “I called APBA and asked, ‘What numbers do you have?’ ‘Well, write us a letter.’ I wanted two numbers instead of three.” Hobart received a reply from APBA headquarters that 77-R was available. “I had that number for 25 years. Started winning more with that boat. We went to the ‘64 Stock Outboard Nationals in Modesto, California. Didn’t do so well. Then the next year we went to Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, for the 1965 Stock Outboard Nationals.

The 77-R in good company at an earlier outboard race. Photo by Bob Carver

That was a trip in those days. Parts of the freeway weren’t finished yet. Just as an aside, Joe Namath and a Seahawk coach, Chuck Knox, both came from there.”

A new hull design appeared at the 1964 Nationals. “It was the first time we saw Hedlund Hydroplanes. They didn’t do so well there, and they didn’t do so well in ‘65,” Hobart remembers. “Basically, they built an A-B. You could run the same boat in two different classes. Now fast forward to the ‘66 Prineville, Oregon Nationals. They won everything. We thought to ourselves, ‘They go pretty well, but I got third—that’s good. We probably don’t need to buy one of those yet, maybe?’”

Getting the 77-R hydroplane ready to run. Hobart held that number for 25 years.

Photo by Bob Carver

Hobart skipped the 1967 Stock Outboard Nationals. The next year, they were held on Green Lake in Seattle. “I won the Divisionals on American Lake in 1968,” Hobart explains. “In those days, if you won the Divisionals, you didn’t have to run elimination heats. I’m sitting there watching eliminations for A Stock Hydro and these Hedlunds are out in front. I’m noticing that a little bit,” he adds with a laugh. “I talked to Ron Hedlund at length about his design and how he came up with all of that. So, the first heat of the finals of A Stock Hydro I get a good start. Flying down the inside, round the first turn, and all of a sudden, there goes a Hedlund. There goes another one. I ended up in sixth place or something. All these Hedlunds were flying by me on the outside. We finished out that year and we said, ‘We need to get one of those.’

There was a guy in Salem, Oregon, named Bill Sterett. He bought the Hedlund that won the Nationals in ‘68. He didn’t like it; he was a bigger guy.

They had the narrower bottom—that’s why you could jack them up and go faster. Found out some of that information from Poppa Smith. The guy Bill Sterett bought the boat from was Mike Mamano, from Florida. His dad was in the machinery-selling business—lathes, milling machines, and whatever. So, on the deck the nameof the boat was Screw Machine. He brings that thing home and his wife says, ‘No, no, no, no, you can’t have that name on the boat there, you can’t have that name.’ He had painted the deck black. Instead of keeping the boat black, I painted it red. My Karelsen was red, and I liked it. We had the Hedlund and it just went faster; now we’re really cooking.”

Hobart was studying mechanical engineering at the University of Washington. In 1973, he evaluated the Hedlund design and decided he could make an improvement, since some new boats had picklefork bows. “I took the decks off one side and took patterns of all the frames. All of their frames were one foot apart. The one forward of where the sponsons end, the lift started there. I just had the idea, why don’t I take that lift design and push it back one frame? Now it starts at the sponson frame. It makes a picklefork because the Hedlund was kind of squared off at the nose. Push that lift back 12 inches, now you have six inches of picklefork. On the Hedlund, they didn’t take time to cut the lightening holes. I took those frame patterns and built this picklefork Hedlund. I used lighter wood. Their frames were made of mahogany and I used aircraft spruce, and a little bit thinner.

Now I’m smoking. I went to the Divisionals on East Park Reservoir, a little bit south of Sacramento. I blew everybody away with this new picklefork. The Nationals were in Utah where the elevation was 4,500 or 5,000 feet—not good. I did terrible there. Come to Lake Lawrence, I got the record. That was a mile-and-two-thirds course, I was a half-lap ahead.”

Things slowed down for Hobart in 1974. He was married, had a young family, and was working for the Boeing Company. And, he said, “My dad had passed away, so I didn’t race very much. I didn’t test, I didn’t run much that year.” Still, he kept in touch with Ed Karelsen. “He was a good friend. He says, ‘I’ll build astraightaway boat for you. Go down to Modesto and see if you can get the straightaway record.’ That boat was a special straightaway boat—basically shallower sponsons and not as much lift, maybe just a little bit wider. So, I went down there and got the record, 60.884. I was pretty much the first guy that went 60 miles an hour with a KG-4. I didn’t own the boat. I gave it back to him and he sold it to somebody.” Hobart continued racing in the A Stock Hydro class; and in September, 1979, on Lake Lawrence, he set the five-mile competition record for the mile and two-thirds course at 55.215 mph.

In the early 1980s, Hobart’s son, Tod, started racing. “He didn’t start at nine, he started at age 12. His mother said, ‘I don’t want him racing, it’s too dangerous.’ We were at Pateros (a small town on the Columbia River in eastern Washington) and Tod knew all the Jones kids. There was a kid who used to come from Michigan and live with Mike in those days. They said, ‘Hey, Tod, put your life jacket and helmet on and take this AStock Hydro out for a run.’ So, he did. He comes back to me and says, ‘Hey, Dad, I want to race.’ We bought a Joe Price J Stock Hydro. I had a J-60 motor and he started to go good with that.”

Hobart continued to race, but following the 1986 season, he decided to step back and concentrate on helping Tod. “He raced A Stock the next year and then he said, ‘With you not racing, I don’t need to race any more either.’ So, we sold everything. I was out of racing for about 15 years. Then, about 2003, I got the hankering to do it again.”

The first thing Hobart needed to do was figure out the best equipment to buy. “I was calling guys around the country, and I called Wayne Seeberg in California. I said, ‘Wayne, what kind of boat should I have?’ He said,‘The guys are winning with Bezoats.’ Shanon Bowman built them. I called Shanon and ordered a kit. Don “Dewey” Anderson and I built it in his garage. It was a C Stock Hydro with a Yamato. I’d never had a Yamato before.

Dewey knows about carbon fiber. They were sixteenth inch decks, three-ply okoume plywood. He put the finest carbon fiber on that, so it strengthened it up a little bit, but it didn’t add much weight. Finished, it was 95 pounds, hardware on it.”

Hobart went to the PRO Nationals in DePue, Illinois. “They were running OSY400. Kind of fouled things up there. But at DePue, I saw these little 125 motors. Single cylinder, alky motor. I hooked up with the Rossi guy and bought one. Never had an alky motor in my life.

Got rid of the Yamato and I was concentrating on that thing. It took a while to get the motor.” Hobart was focusing on racing in the UIM Worlds in Lakeland, Florida, in late September.

Hobart and a friend were waiting anxiously for the 125 engine to arrive. It was the weekend of the Lake Lawrence record race. “So, heck with it, we’ll just drive down to Lake Lawrence and watch the race,” Hobart remembers. They were on the way to Lake Lawrence when Hobart received a call on his cell phone. “It’s Rusty Rae. Somehow, he’d been tracking the engine. He said, ‘Hey, your motor is at the UPS warehouse in Issaquah.’I said, ‘What?!’ So, made a U-turn, went there and picked up the motor.” The next step was to cut down the transom on his Bezoats so the 125 engine would fit. “Drove to Dewey Anderson’s shop because I had the key. We started cutting down the transom and putting the throttle on, the pipe puller and things. All that was foreign to me. Now it’s about 6:00. We kind of looked at each other and said, ‘We’ll just finish it in Florida.’” They packed the trailer and drove back to Hobart’s condo. “We threw some clothes in a suitcase and took a shower. We left Bellevue at midnight on Sunday. We were in Lakeland, Florida, at 6:00 p.m. Wednesday. Almost 4,000 miles, straight through.

All too soon, Hobart discovered he was up against some tough competition. “I didn’t do very well. We’re talking about world-class people who were coming to that event. I don’t know why I thought I was going to do anything.” Hobart tried running the 125 for another year. “Bought another boat that was really designed for it. Spent quite a bit of money. Naw, I’m not an alky guy. You’re constantly tweaking with stuff. I’m a stock guy. You set the carburetor and wait for the five-minute gun to go off. So, I got rid of all that stuff. Then I didn’t have any equipment.” He thought about which direction his racing should go. “I could probably get into a 45SS and race.” Hobart called Dan Schwartz, who referred him to Revolution Tunnel Boats. “I called the guy and said, ‘I want two of them.’ This is about 2010. He built the boats. He built a special double-decker trailer.”

When Hobart took delivery of the boats, reality started to set in. He makes a disappointed sigh. “Looking at that, I said, ‘You know, I’m not going to be able to do that.’ I was working at Boeing and Jeff Kelly was there. I was always going over to his place at Boeing. We’d b.s. for a while. By this time, I knew how good J. Michael Kelly was. He’d race a piece of plywood down the lake if you’d give it to him.

I said, ‘Mike, do you want to drive my 45?’ ‘Yeah!’

Corey Peabody in Hobart’s tunnel boat #70 at Eatonville, Washington, Winternationals, 2011. Photo by Gleason Racing Photography

“I bought some motors here and there. Got one good motor from R.J. West, a good Jerry Wienandt motor (he was building good stuff). Plus I bought a bunch of propellers from one guy who was getting out. They were really good propellers. He had 1, 2, and 3, so 1 must have been the best one.” The Divisionals were in Oroville, California. “We got this stuff in the pits at 6:30 in the morning. J. Michael was going to run it and he says, ‘Put that propeller on,’ the one that had the 1 on it. R.J. West was there and he kind of set it up. J. Michael had never been in a tunnel boat before. He’d never used the up and down buttons, the in and out kick-out, never used those before. At 4:00 in the afternoon he was Divisional Champion. Ain’t that cool? We messed around with those for a couple of years, J. Michael and I. It was getting kind of expensive—that double-decker trailer, two outfits and all that. I sold it to the APBA Drivers’ School.”

J. Michael Kelly in Hobart’s tunnel boat #777 at Eatonville, Washington, Winternationals, 2011. Photo by Gleason Racing Photography

Hobart pondered his next move. “In (early) 2014, Howard Anderson passed away. We were at his service and J. Michael says, ‘A bunch of guys are getting into C Mod.’ ‘Okay, let’s talk to Dewey. How wide do you think it ought to be; how long do you think it ought to be?’ We figured all that out. He built the boat, and I put that whole outfit together in less than six months. Got the powerhead from Mike Ward in England. He was a Yamato dealer. Somebody else worked on the foot (lower unit) because you could take that Yamato foot and put a nose cone on it, to streamline it a little bit. We ran it a couple of times around Region 10 and then the Nationals were at Moses Lake, in 2014. He won! We go back to Constantine about two years later. He won there. So, in the last six to eight years, we’ve been to the Nationals four times, and won them all. This year we got second, because the motor is just not running well. It has to be gone through, or something.”

Hobart’s association with the Kelly family has an interesting history. One of his early rivals in A Stock Hydro was Ron Shew. “He had the same Karelsen kit boat that we did. It was him and his dad, me and my dad, kind of a dad and son deal. We got to know them quite well. Tim Kelly, who is Jeff’s father and J. Michael’s grandfather, lived with the Shews. I don’t know why his name changed to Kelly. Tim and the Shews were racing A Stock back in the 1962 era. That’s where I knew him. Jeff would always come to the races, so we knew each other way back.”

Dean Hobart’s life has revolved around outboard racing for more than 60 years. As a driver and later as an owner, he has set records and won championships. With a lifetime of stories to tell and memories that would fill a book, he is what boat racing is all about.

Featured Articles