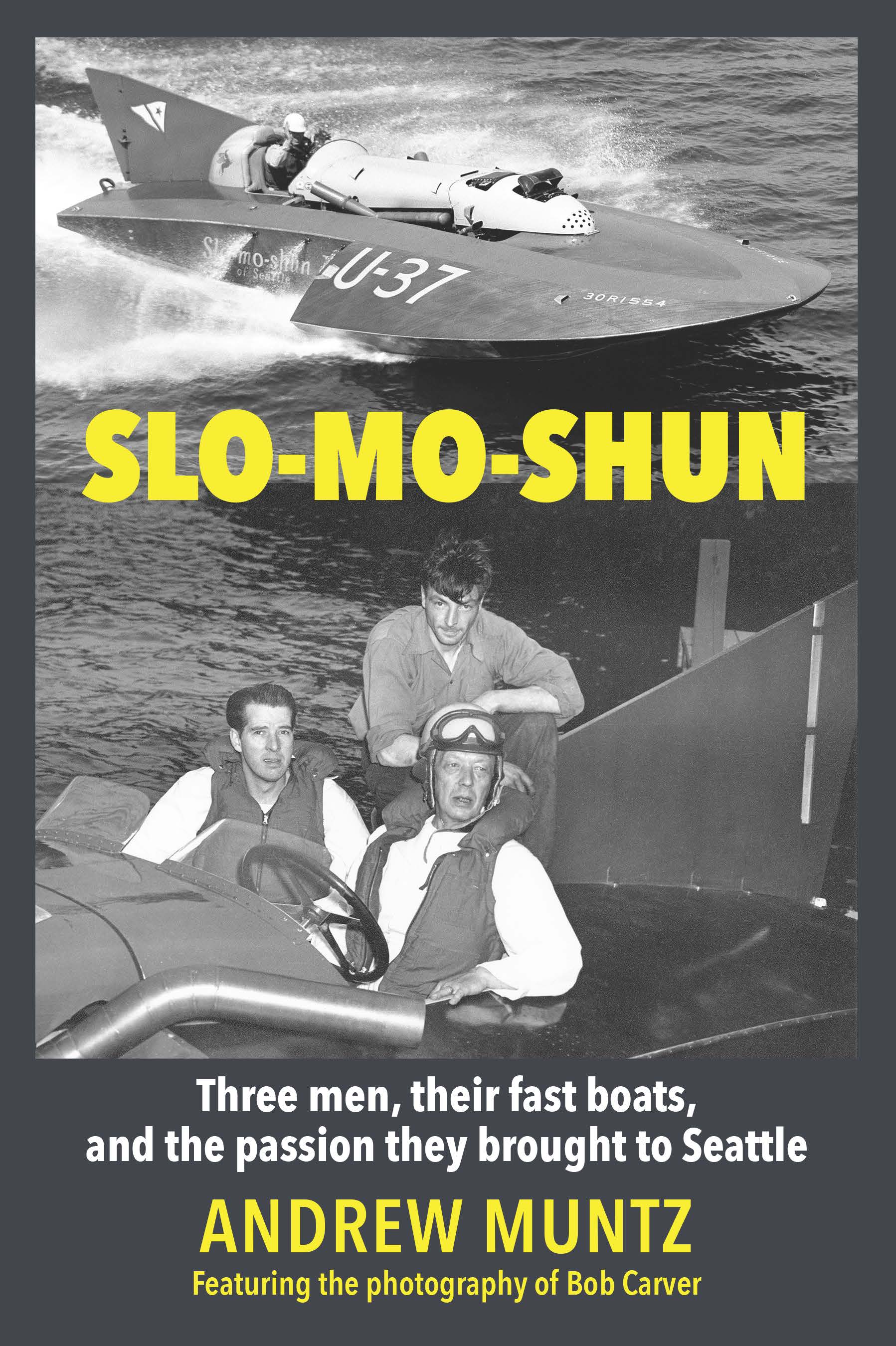

In the Water with Wade

May 8, 2024 - 3:32pm

Wade in the Water- photo by Jack Cool.

In the Water with Wade

by Craig Fjarlie

Photos from the collection of Wade Williams except as noted.

Wade Williams was a 280 driver from Seattle. His best-known boat was named Wade in the Water, but he drove other 280 inboard hydroplanes as well. He grew up during the heyday of hydroplanes and attended the 1951 APBA Gold Cup on Lake Washington when he was eight years old. He knew someday he would have his own boat. “I did the whole bit, towing boats behind a bicycle and that kind of thing,” he remembers.

Williams became a fan of Harry Reeves, who had a limited boat named Ope. Reeves also drove the Unlimited hydroplane Coral Reef. “In 1958 they had the Inboard Nationals here and I followed him. I didn’t know him; I just cheered him on,” Williams explains. “Well, 10 years later I went to work for Boeing and ended up working with Harry Reeves.”

Williams did a stint in the Navy right after he finished high school. “I was 17 and went to electronics school for six months. Then they sent me to Guam. It was funny—when we first got to the school somebody had carved in the desk, ‘Here today, Guam tomorrow.’ I was there for 15 months, then I came home and was on the radar picket ship.”

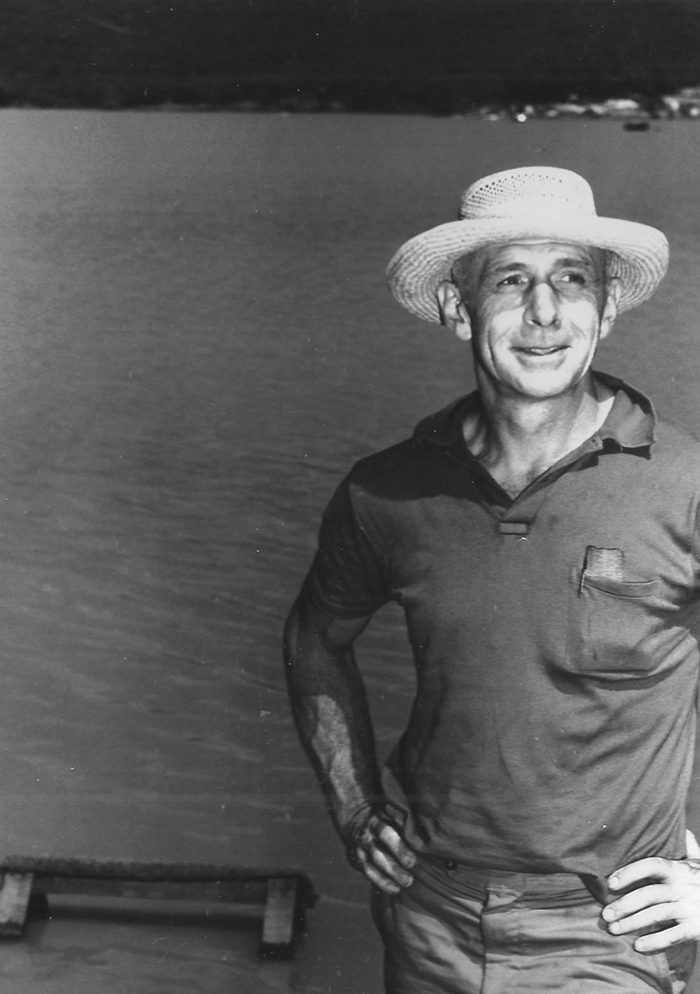

Wade Williams.

Following his discharge from the Navy, Williams attended the University of Washington. “I majored in English, although I did not graduate. I ended up going to work for Boeing as an electronics technician. That dictated my career for almost 20 years.”

While working at Boeing, Williams talked with Reeves about racing. “I said to myself one day, ‘I’ve always wanted to race boats—why am I not racing boats?’ I went out and bought a hydroplane, which turned out to be one that Reeves had previously owned. It was a 225, built in 1955 by Rich Hallett. I was at a race at Lake Sammamish in 1968 and the boat was for sale. Harry suggested I buy it because he knew it was a good boat and we’d make it into a 280. I bought the boat and trailer for $600, and then had to find a Chevy engine, a 265, to put in it. I called it That Boat, E-329. That was kind of my trainer boat.”

That Boat on Lake Sammamish, the first time Williams drove it.

Williams has clear memories of the first time he drove the boat. “We went to Lake Sammamish and Harry took it out first. He came back and told me he went 85 miles an hour, about 5,500 rpm. So, I went out and of course I’d never been in a hydroplane and I’m doing a hundred miles an hour, it seemed like, going down the lake. I came in and there was another boat racer named Pat Berryman. He came down and said, ‘How fast did you go?’ I said, ‘Well, Harry said he went 85 at 5,500. I think maybe the speedometer broke because I was turning 5,500.’ He said, ‘What did the speedometer say?’ I said, ‘It said about 55.’ He said, ‘That’s about how fast you were going.’ I said, ‘Put some gas in this.’

We filled it up and I aimed it down Lake Sammamish, put my foot down and it stayed there until I saw 85 miles an hour. That was my introduction. We kind of laugh about that.”

Given the boat’s age, Williams had to make numerous repairs. “It was old; there were problems,” he admits. “Blew out the bottom at Harrison Hot Springs. I broke the seat five times on the right side, just trying to throw me out. It was a good trainer boat.” Williams was having fun learning to race when Boeing sent him to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “The first weekend I was there I went down to see Ron Jones in Costa Mesa, and asked him why his boats went so fast. He spent four hours showing me everything. I went home and told my wife, ‘Well, we’re not going to race the old boat any more.’ I sold it to one of my crewmembers and ordered a Ron Jones 280 hydroplane. We decided to paint it in Ron’s colors—white, orange, and metal flake brown. It was called Wade in the Water, E-35.”

Wade in the Water at Ron Jones’ shop in Costa Mesa, California.

Before Wade in the Water was ready, Williams drove a 280 named Miss Anglee. The owner of the boat moved from California to the Pacific Northwest. “I flew up here to drive it,” Williams says. “I talked the owner into letting me drive. Had not been in a boat for a year. No test time at Green Lake. They had 21 280s, so three elimination heats. You were first, second, or third, or you were out. The tenth boat was the fourth place boat with the fastest elapsed time. I ended up getting three straight thirds. In the final heat I was actually in second place until I hooked the boat and almost went out of it in the big turn. Calypso went by me, so I finished third. Bruce McDonald set a World Record in the Karelsen Special, so that was good.” The boat Williams drove had a rear cockpit. “It was a floating massage parlor,” he jokes. “They had to help me out of the boat after the first heat because it beat me up so bad. The life jacket climbed up my back and was compressing my chest. After I drove it, I introduced the owner to John Leach, a great 280 driver and owner. He drove it the rest of the year.” The boat was later sold and passed through a couple of hands. It is currently being restored by Skip Govia.

While racing Wade in the Water in California, Williams found the courses were quite different from the ones in the Pacific Northwest. “It was challenging down there,” he says. “I had to learn how to drive the boat on the smaller courses, but I did pretty well. I was the 1972 National High Point champion in the 280 class. I was not just another boat racer. I came up to race on Green Lake every year. Never won a race there, but I did finish in the money a couple times. You came to a place like Green Lake, you just put your foot down and left it there for three laps. It was fun—all your friends were there—but it was actually kind of boring as a racing experience.”

While Williams was racing with the California Speedboat Club, he won a trophy at Oakland that had a long history. “On the Fourth of July they had a special one called the F.W.

Barron Trophy race. Big, sterling silver mug. Had been won by Lou Fageol and Dan Arena. I won it two times in a row, and I got my name on there with all those others. The Barron race was 10 laps. It was open to any of the hydros, so there were some 145s and they’d run until they ran out of fuel. I was running with one boat and I think he had a spark plug wire fall off. I was trying to make it look competitive, so I was just staying ahead of him but doing 65 miles an hour. I picked up enough to beat him. My wife at the time said, ‘You just had to look at the boats and you knew who was going to win right away.’”

Wade in the Water in 1973, after mishap in Parker, Arizona. Photo by Russ Price.

During a race at Bakersfield, Williams won the first heat and lapped two boats. “Ted Jones was there. He came over and said, ‘Well, Wade, that was pretty impressive, but you gotta be careful about doing that too often because pretty soon you won’t have anybody to race against.’”

Williams had a few mishaps with Wade in the Water. “I was once at Parker, Arizona, which is very warm and hot. The final turn, I made a last-ditch effort to get this guy. Skipped sideways, blew in the non-trip and part of the deck, and got hit with water and spray. When it cleared I was still on plane and going, so I crossed the finish line and drove the boat up on the beach. (I was a trailer launcher.) I jumped out and started doing a rain dance, hoping it would rain and I could get second place.”

Williams drove both conventional boats (with the cockpit behind the engine) and cabovers. “Cabovers were a different experience,” he confirms. “Up in front is like sitting in a rocking chair. It’s a lot smoother. I spun the boat a couple of times, a 180 and all. In front, you’re closer to the pivot point so it’s not as much g-force. Sitting behind the engine, I’d have been tossed out for sure, but it also gave you a false sense of security because you weren’t sure what was going on behind you. George Henley liked sitting behind the engine, slamming elbows, banging knees. That was real boat racing to him.”

When Williams decided it was time to stop racing, he sold his boat to someone in Alaska. “He didn’t do too well with it so he sold it back to somebody down here. Jeff Babcock drove it once at Lake Tapps and he got a hole in it and sank it. The last time I saw Wade in the Water it was sitting at Ron Jones’s shop in Kent, Washington, with the deck off. It was sitting on the ground. I have no idea whatever happened to it after that.”

If Williams has one regret, it is that he never had an opportunity to drive an Unlimited hydroplane. “I hoped to drive Unlimiteds like everybody growing up in Seattle,” he admits. “I did make an effort in 1974 to drive Miss Van’s P-X, owned by Bob Patterson. I actually went to his shop and got to sit in the cockpit. It was behind the engine then. It was a turbocharged Allison—you had to look around it, couldn’t see over it. My friend Jack Schafer beat me out in the end because he had an airplane. It would have been nice to drive that boat, but I didn’t pursue it. Just sat in the cockpit and dreamed about it.”

Williams remained involved as a crewmember on Misty Lady, a new Jones 280 owned and driven by Pat Patterson. “Ron asked me to go out and help Pat if I could, because he didn’t know anything about boat racing. So, I did, in 1977. He won one race—the only one I didn’t go to—and I think that’s because somebody flipped. It was frustrating because it’s hard to explain how to drive the boat until you do it and feel it. It was a really good boat; he had first class everything. He learned, and in 1978 he had a new engine built by John Leach. He went down to American Lake to test and broke the crankshaft. He had to get another engine and he never called me back. I’d hear these stories, all the misadventures he had during the year. Then at the end of 1978 he called me and asked if I’d come back and help him again. We had a long talk and I agreed to do that. We spent all of 1979 basically putting all the old wives’ tales to bed, you know, advancing cam shafts, retarding cam shafts, spark, all that kind of stuff. At the end of the year, we decided we’re doing this all wrong. He always talked about being water ski champion at Lake Tahoe when he was in college. Had this big Cadillac engine with a big three-blade propeller and would really accelerate. So, he had Mercury take a 7-Litre propeller, because it was a big propeller, and modify it for our propeller shaft. It had a lot of lift in the back, so we moved the engine back a little bit. We took about 10 percent of the weight out of the boat. We took out the original seat which I think weighed 19 pounds and put in a seven-pound honeycomb aluminum seat. We put 145 cowlings on the boat, we just cleared the valve covers, so it made less frontal area which is less drag. The one thing I remembered from physics class in high school was force is mass times acceleration, and acceleration is force divided by mass. Next year we won 12 races, just totally dominated. He was doing the driving, had gotten pretty good.”

Pat Patterson’s Misty Lady. Wade Williams was a crewmember on the boat.

Williams and Patterson knew propellers were a key factor in a winning boat. “We went back to the Mercury factory in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, in October of ‘79,” Williams says. “We tested 23 propellers as I recall. We had a box of them in the boat and I would change them underwater—we never brought the boat in. The test was how fast we could get from 70 to 100. Mercury was surprised at the differences in some of their supposedly identical propellers. We could go from 70 to 100 in 7-½ seconds. Everybody else was taking 11 or 12 seconds. That’s one reason we won 12 races. With the engine back the boat was flat, it didn’t get flighty at the end of the straightaway, which you’d have to settle it down. You just hang it on the skid fin. It didn’t have the top speed of some of the other boats. We’d turn 5,500, 5,700, and the other guys were turning 6,200, but that prop, it was just a rocket.”

Patterson wanted to make changes to the boat for the 1981 season. “He wanted to lower the engine, the shaft angle, which meant putting in a belly pan,” Williams remembers. “He owned the boat, so he lowered the engine and he screwed the boat up. Only won six races the next year—it just wasn’t the same boat. He sold the boat, but I give him credit for not sitting on his laurels. He was trying to get better.”

Patterson and Williams knew Ron Jones was developing new designs, so they opted to sit out the ‘82 season to see what the new boats could do. Patterson ordered a new boat for the ‘83 season. “I remember we first tested at Lake Tapps and Ron Jones, Jr., was there, as well as Ron,” Williams says. “The boat was just a rocket. Ron Jr. said, ‘I think you got ‘em covered.’ It was a really, really great boat. We were National High Point champion with that boat, and we won two National Championships.”

Williams made one contribution to Unlimited hydroplane racing. “When they were building the 1979 Miss Budweiser, they didn’t like Ron’s cowling design. They had David Smith, who had done the Atlas Van Lines for Bill Muncey. He worked at Physio Control and had them do a design. I saw it on paper and Ron said, ‘It looked like a Porsche.’ He didn’t like it, so I brazenly told him, ‘Well, I’ll do it.’ So, I had a model made of the center section of the boat, one inch to the foot in carbon and foam and put some fiberglass on it for rigidity, got some modeling clay and modeled a version. I took it down to the shop and a fellow named Wes Carmen, Ron’s son-in-law, a 225 driver, came and looked at it. I could see the expression on his face, he didn’t like it. I said, ‘I’ll do another one,’ so I did. Came back and that’s the one they ended up doing. Ron asked me if I could do the drawings on it. So, I had to measure the clay model and make an inch to the foot drawing, and then scale it up on Mylar, the full size and all the frames. It had the scoops that came down the sides and back. Bev Jones thought it looked like a pregnant puppy. Dave Culley told me Ron never liked it either, but he never told me that. It wasn’t his cowling. But it was distinctive, and they had wanted something different. I remember Dave told me somebody came up to them and said, ‘Boy, that’s a lot of lift in that cowling, you must have done some wind tunnel testing.’ Dave said, ‘Oh, yeah, we did testing and all that.’ Well, of course, he knew I did it all on my kitchen table. They did lose it at a race on the Ohio. The tie-downs weren’t tight enough and it lifted the sucker off. I had to make another one in a hurry.”

Williams has memories of other racers. He became good friends with Harry Reeves. “He was the most competitive person I’ve ever met. He retired and we used to play tennis together—doubles—and he liked to golf. We were playing ping-pong at a party once and I dribbled the ball over the net for the final, winning point. He threw his paddle at me. He told me when he went into the first turn he would never look to the left or the right, and they knew he wasn’t looking and they’d have to get out of his way. He found out he was going to drive Coral Reef when he read it in the newspaper, right after he won the Nationals in ‘58.”

Williams occasionally worked at Ron Jones’s shop, helping with various projects. “Mike Hanson worked in the shop when I was there and he occasionally screwed things up. They had to do it twice. But he did learn and he did pretty well. Won the APBA Gold Cup. Tip my hat to him.”

Of course, Williams knew Pat Patterson well. “I learned a lot from him. He’d gone to Stanford, one of his roommates was Nick Reynolds of the Kingston Trio. Pat had been in the Marines before that. He’d always been very successful, including everything he’d done in high school. I went to his parents’ home; he went back there once. They had a bedroom with all his trophies and accolades. When he got to Stanford he found out there were people a lot smarter than he was. He almost had a nervous breakdown. He knew if he was going to succeed, he had to do something nobody else wanted to do, and it was truck parts. When I met him he was the national parts manager for Kenworth, later fleet sales. I remember he did a $20 million deal with Roger Penske. He was real gracious in the way he would treat people. He would tell you anything you want to know, and would tell you the truth. Well, Pat died a couple years ago,” Williams adds, with a note of sadness.

Looking back at his involvement in boat racing, Williams has no regrets. “It was fun, but it was dangerous as hell. I knew 22 people that were killed. But it was exciting. If I were to win the lottery would I do it again, go buy a boat? I don’t know. Canopies kind of turn me off, but it’s certainly safer.” He is a frequent visitor to the Hydroplane and Raceboat Museum, and will talk about racing with anyone who shares his interest.

Wade clearly regards boat racing as his extended family.

Wade in the Water- photo by Jack Cool.

Featured Articles