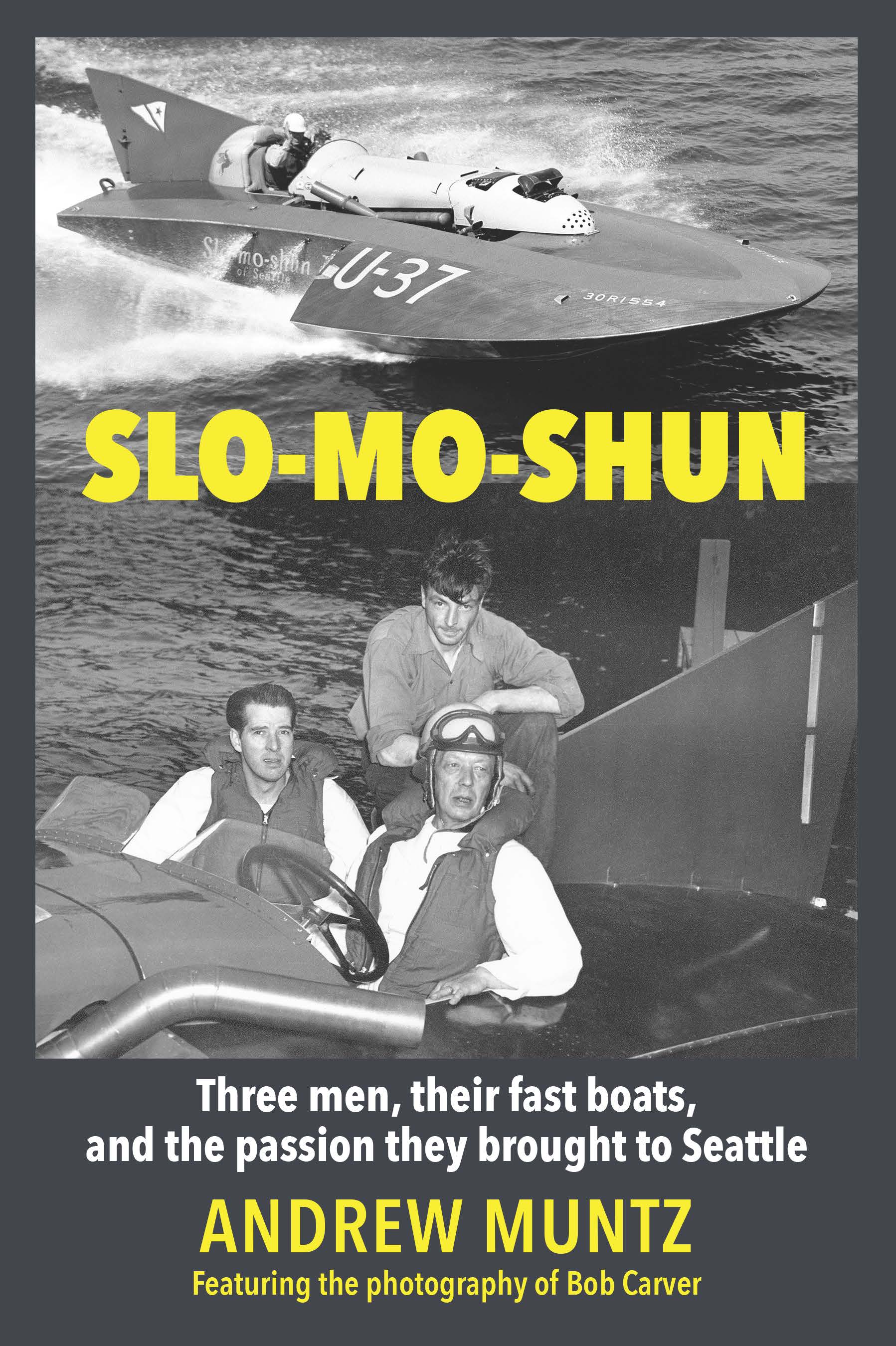

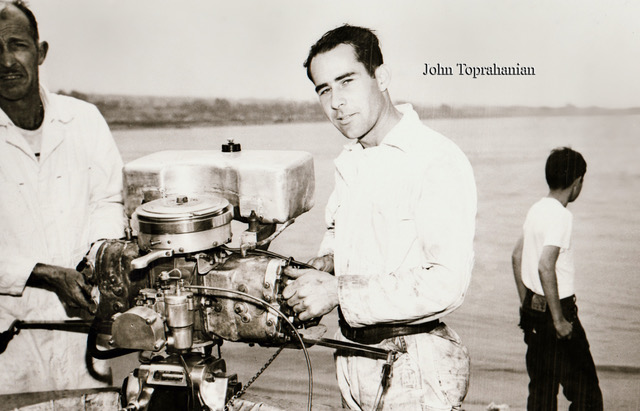

John Toprahanian

May 27, 2024 - 7:37pm

(L) text from Outboarder and (R) The Antique Outboarder Archive 1974

Thanks to Jay Walls, Todd Brinkman, Alan Ishii, Mike Hodes, and Fred Truntz for their contributions to John Toprahanian’s history.

Photo credits go to Jay Walls.

From Todd Brinkman May 16, 2024:

APBA PRO Nationals, Winona, Minnesota 1976. Fred Brinkman (Todd’s grandfather) ordered a new Speeditwin C Service engine from John Toprahanian. Fred’s procedure was to order engines and notify the other family members when really necessary. They brought this engine to Winona in 1976. While testing, Todd found the Speeditwin to be 1-2 MPH faster than their other engines. (This engine had narrow bypass cylinders.)

After the test, Bob Rake and Fred W. (Todd) Brinkman (Todd’s dad) removed the cylinders, filed the spots on the piston deflectors where they were contacting the radius of the cylinder, then re-installed the cylinders.

Heat 1 went to Hal Tolford, 2nd Todd Brinkman (starting 6th), 3rd Pete Hellsten. (Hal Tolford, Red Taylor and Pete Hellsten were running exceptionally fast 2-cylinder Mercs.)

Heat 2 went to Todd Brinkman, 2nd Pete Hellsten, 3rd Hal Tolford. (Todd’s start meant everything.)

Todd Brinkman won the 1976 C Service Runabout Nationals – nice 18th birthday present. The following week, O.F. Christner called Todd’s grandfather Fred to ask if Todd would drive for Quincy the following year.

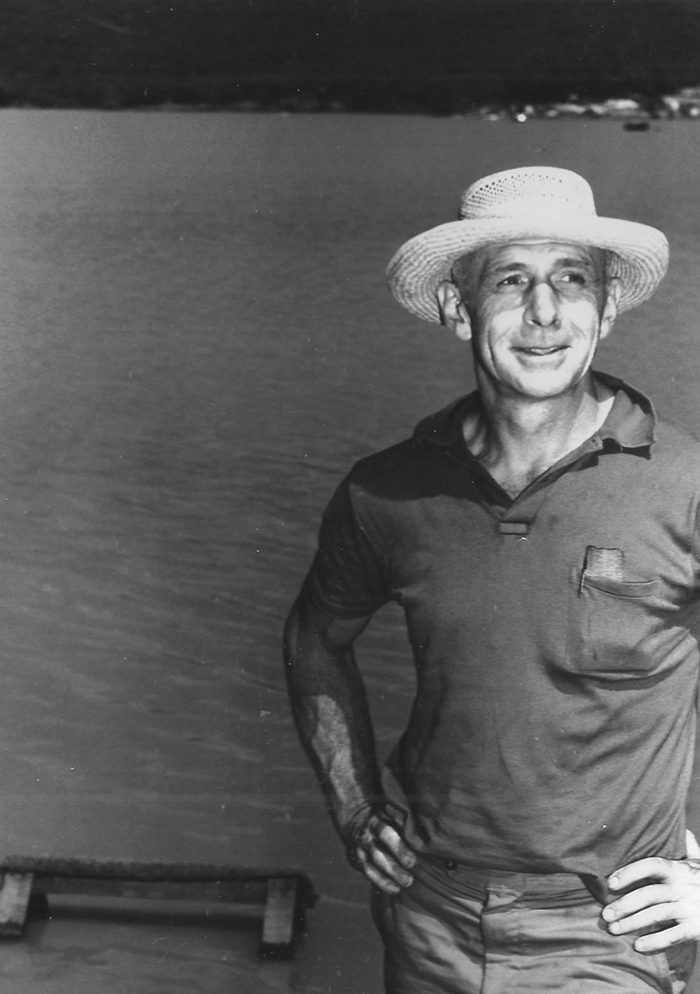

John on the beach

From Mike Hodes:

I’ve been hard at it revarnishing the 1929 Wason.

Here are some memories of John Toprahanian.

In about 1994, when I was in San Diego on business, I spent the day with John Toprahanian. John was working on a Model T Speedster Ford engine, doing extensive modifications. I was amazed at his ability.

We talked about building a fast Big Four cruiser. I had many questions about building a strong Big Four. I asked John how he and Pep figured things out, and John said they would build it and then put it on the dynamometer and test it. It was all “build it and test it and develop it,” and this took time and patience.

I came back a few months later and spent some more time with John. As we were saying goodbye, he said he would build me a Big Four powerhead once he was finished with the Model T.

We talked about hundred horsepower rods and 2-ring pistons and changing the rotary valve timing to 70 degrees. John also suggested a Winfield carburetor, turning the engine 5800 RPMs, and the heavy flywheel.

I was thrilled, to say the least.

As I understand it, John did finish the Model T and passed away soon thereafter.

John was very kind and patient, and helped me understand the Big Four.

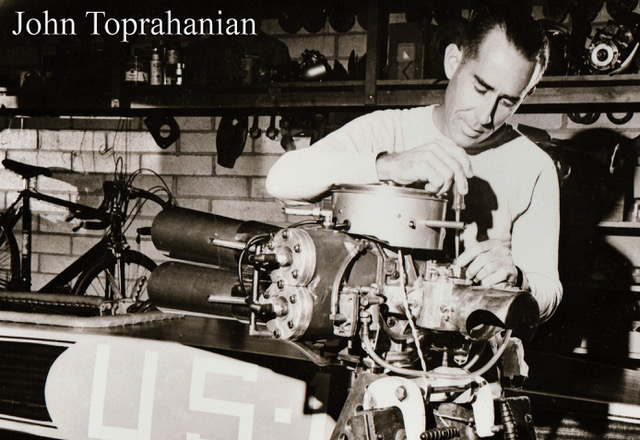

John with his famous F/ 4-60 with Winfield carb and Hubbell pipes

From Fred Truntz:

I was introduced to John Toprahanian in 1982, soon after I joined AOMCI. We were friends until his passing in 1995. We never met in person, but exchanged letters and phone calls for all those years. During this time John was actively restoring and building 4-60 engines for the people restoring vintage Midget race cars. Two of his major projects were building a right-angle gearbox that the 4-60 mounted to for installing in the Midget race car, and a carburetor with a barrel valve that uncovered holes in a spray bar as the barrel valve opened. John used Winfield float bowls he found at flea markets to build the carburetor. His design featured high speed, low speed, and midrange adjustments; and was an improvement over the Vacitiuri A500 carburetor. His carburetor was used on the 4-60 on race boats as well as Midget race cars.

California EPA requirements closed many of the small foundries that John had used to make his castings. My friend and fellow AOMCI member Ed Griggs owned an aluminum/bronze foundry here in New Jersey. John would send his patterns from San Diego to New Jersey; we would cast his needed parts and send them back for him to machine. In appreciation, John often sent packages with all sorts of surprises. One surprise was a box of parts to assemble an Evinrude hex head powerhead. Another held parts for Evinrude Speeditwin C Service parts. And he sent all sorts of other ‘goodies’…

My enthusiasm for early race engines far exceeded my knowledge about them. John was always ready to share information and take time to explain things. I appreciate all that I learned from him. I have saved many of his letters that explained how to do things and why, as well as providing information on all of the early race motors, boats, drivers etc.

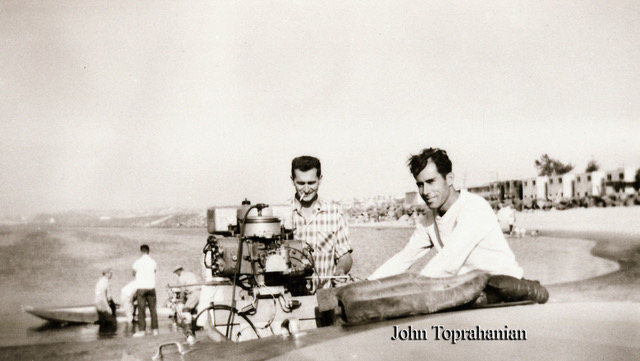

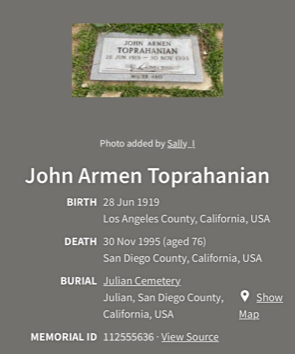

John coming in

From Alan Ishii:

Writing about John displays how good a machinist and craftsman he was. Wonder who ground the cranks after carburizing? After many years, I got to ride in the C 12 with the late, great Dean Wilson. He was a very good driver. I wanted to ride with George May but my dad would not let me.

The throttle looks like it would be easier to hold without twisting your wrist. Apparently Ralph did not make many, as this is the first I have ever seen.

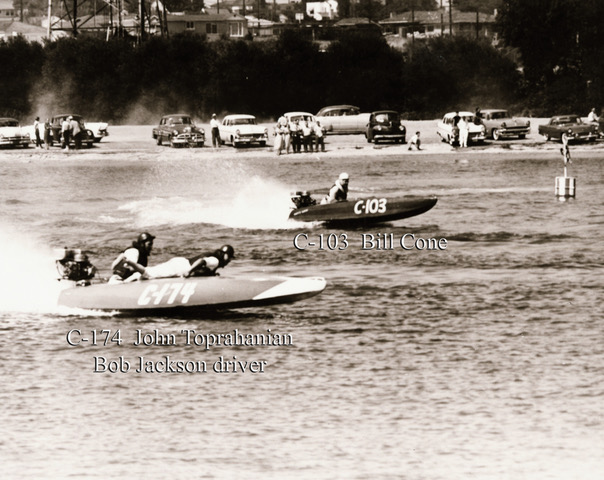

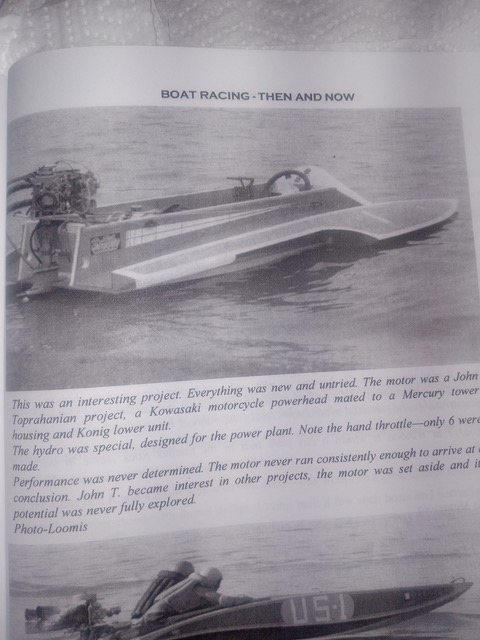

I have some pics of John’s B Hydro from Ralph’s book. Note the horizontal throttle. I liked it! I think it was a Yamaha, not a Kawasaki.

John had a 350 hydro he let me drive a couple of times. It may have been the first motorcycle engine conversion(?). It was a gas-powered Yamaha road racing engine on a DeSilva hydro, with a Konig lower unit. There is a photo in one of Ralph’s books. Ralph and Bill also designed a horizonal throttle. It would be perfect for today’s laydowns.

There have been marvelous innovators in our sport. John was one of the best.

John Toprahanian changing plugs every heat

John Toprahanian Part 2 by Jay Walls

As outboard racing became popular, motor builders like Tom Newton, Walt Blankenstein, Stan McDonald, Marshall Eldredge, Dean Draper, Frank Vincent, Dick Neal, and Fredrick (Perk) Perkinson were key innovators—along with a host of others who built engines for hire. I reference the “old guard” engine builders, not the younger ones (some of whom are in their early 90s). Walt Blankenstein built different class motors, but primarily stuck with the Johnson rotary valve engines. Tom Newton and Stan McDonald were best known for their knowledge of C Service engines.

Dean Draper did porting and modifications on whatever came to his shop, but was known more for his “F” class work. Dean built four of his own “X” class engines. When World War II began, Dean converted his shop to making whatever he could to help with the war effort. He never got back into racing outboards.

Fredrick Perkinson did the same type of work as Dean, and also built an “X” motor that P.H. Cornwell was going to use to set a world speed record. When the day came, P.H. had bought a new Cadillac to pull the trailer. However, as his mechanic wired up the car for trailer lights, something went wrong and the whole rig burned to the ground.

Marshall Eldredge made some of the best-known engines of the early era. He also made an “X” class engine utilizing his own crankcase and PR components. Frank Vincent and Dick Neal built engines for all classes, but were known mostly for their work with “B” class on up to “F” class.

Some of these noted engine builders made their names before the War and some after, but there were only a few who stayed with engine building their whole lives. John Toprahanian was the guy that other engine builders went to with questions as more technology came into building racing engines.

John lived in San Diego, California and was part of the great West Coast boat racing scene. John was a great friend of Randolph “Pep” Hubbell, and had access to parts Hubbell. He also had an in with the Evinrude factory, and could get parts for 4-60s long after they were discontinued. John had a knack for machine processes; after something was explained to him once, he could go home and duplicate parts and improve them as he wished. John was bothered by unpredictability in an engine. He would put effort and time into an engine and then sometimes find it not to perform to his liking. John theorized that as the engine ran and made heat, the round bore of the cylinder would deform and thus get inefficient. Some would call this just plain slow. John started cutting up cylinders, measuring cylinder wall thicknesses, and keeping a great notebook on all he was doing. His theories on bores proved true, as he found that he could consistently build fast engines if all the criteria on cylinder wall thickness were followed. John tested engines, made little changes while testing on Hubbell’s dyno, and recorded his findings.

John could help you with all classes, from a Midget racer right on up to his true love, the Evinrude 4-60. As Hubbell made parts and rebuilt engines, he and John would test them on the dyno and record everything. They recorded statistics on every engine that went through the dyno room, then used the notebook to help fellow racers. John Toprahanian was one of two boat racers I have known in my lifetime who didn’t mind telling fellow racers what it was going to take to beat them. The other was Harry Brinkman. He not only would tell you what you would need to do, he wrote it all out in a manual—then revised it twice as he found new speed. Harry didn’t mind letting you know what it was going to take, because according to him, even given all the information, guys would still shortcut the steps and procedures. Thus Harry was confident he could still win on the racecourse. John once told me that anything I could think of had been tried or tested on the dyno.

My dad, Emmett Walls, was a machinist in his own right and he would write to John all the time. John would send a postcard or a letter in reply. I remember Dad calling at 12:30 each day to find out how our day was going. It was exciting to tell Dad he had received a postcard from John, and then Dad would ask what the postcard said. My answer was always the same—I couldn’t read it and had no idea. Others in the Antique Outboard Motor Club had the same experiences with John’s postcards. Hungry members who had just found a racing motor would contact John to ask what to do to get it running or restored. John must have written thousands of these postcards, and I have a shoebox full of the ones he wrote to Dad or myself.

John had a love for Indy 500 racers, and A.J. Watson was my next-door neighbor in Speedway where I grew up. John came to our house for the week of the race several times while I was growing up. Those times were spent at the track, and in the basement where the 4-60s were kept. I drove a 427 Ford Galaxie back and forth to high school, and John always got a kick out of some of the stories I could tell.

John hated Vactiuri carburetors; he likened them to toilets. He blamed the Vactiuri for all the fouling while milling around waiting for the race to start. He hated them so much he made his own smooth bore carburetor that utilized the Winfield spray bar. It instantly eliminated plug fouling. He used his carburetor on his 4-60 but soon it was outlawed. John tried, and for some time did have his carburetor approved for racing, but I believe it ended up being outlawed. John made many of these carburetors, and they are a prized find among antiquers of today.

John Toprahanian, right, with trophies

John never gave up on the 4-60 design when it came to boat racing. After the 4-60 was getting beat by the newer Mercury and Konig designs, John designed and installed a megaphone exhaust on his 4-60 and gave fits to the competition. As other technology came into play, like the Looper and reed valving, John kept the same Evinrude 4-60 crankcase, milled off the front of the case, and installed a huge reed valve box. He then took Yamaha motorcycle cylinders, which were of the Looper technology, milled the cooling fins off, and installed water-cooling jackets so they could be run on a boat.

Hubbell was sitting on lots of lower unit castings that were not being used any more, and John found that he could mill two sets of castings into a more modern shaped unit and use more modern gearing. These units, along with the motor John affectionately called the Yamarude, kept up with the competition clear into the 1980s. These Yamarudes would turn over 10,000 RPMs and run well over 100 MPH. It was reported that they would come off the corner and instantly be over 90 MPH. They competed in the PRO Alky category’s 2-man 1100 Runabout class.

John’s death was somewhat of a surprise, as he was still doing work and still had plans for driving his just-finished Model T Speedster with a Frontenac overhead valve conversion head. John had worked on this busted-up head, that really was a throw-away, for what seemed like 20 years. John also had a 1934 Ford truck he ran around town in.

John’s 1934 Ford truck in 1984 at an antique Ford dealer’s annual Xmas party with over 100 cars to the right.

Some people have interesting sayings or prayers on their headstones, but John’s headstone is as meaningful as any.

John Toprahanian, San Diego, California June 29, 1919 – November 30, 1995 (76)

John Toprahanian of Armenian descent, U.S. Navy veteran, boat racer, engine builder, automobile restorer, researcher and sharer of information he had acquired from many years of experience.

John T., start of F Runabout

John and friends with trophies

John deck riding with Bob Jackson

John Toprahanian

From Alan Ishii:

Wonderful history of a man with a true love for boat racing. What a craftsman! I also remember he had an old El Camino he used to trailer to the races.

Did he heat treat the cranks?

Not much to tell about John’s B Hydro. I think he was helping Yamaha develop the engine for their road racing program? Yamaha racing was in San Diego. He ran it on gas. That’s why I think he was working in development. He had it on a Konig lower unit. There is a picture of the rig in one of Ralph’s books.

John’s B Hydro made with a Kawasaki motorcycle engine

What was unique about the boat was a horizontal throttle that Ralph and Bill made. They said I was the only one who liked it. The boat ran twice at Bakersfield. Ran great. For some reason he stopped running it. Maybe Yamaha pulled the plug?

My first encounter with John was when he came up with the idea to core check cylinders for being straight and consistently thick. Over the phone he instructed me on how to build a box to hold the cylinders. This was different than one would expect, as the cylinders were bolted to the lid. This box was built with 3/4” poplar plywood. I still have the box; only the lid has been replaced. This was also during a time when the cost of shipping heavy cast iron parts was far more reasonable than today.

John would cut off the water jacket, turn the o.d. of the actual cylinder round, then make a brass sleeve to fit over the newly turned surface with grooves cut in the brass for additional cooling. His goal was to have a straight cylinder, cooling equally around the circumference and staying straight while running. If all these things happened, the cylinders would perform better than before.

John proved his point when he built Todd Brinkman a C Service Speeditwin for the August 1976 A.P.B.A. Nationals at Winona, Minnesota. This engine had narrow bypass cylinders and won both heats well in front of a full field of boats.

In one of his (undated) letters he stated: “To be simplistic on cylinder hot spots, it’s like frying an egg—the yolk never burns, being so thick. All this sort of thing is in engineering books, especially Ricardo of England. Vincent sand cast pistons were the thickest and the least trouble. Later, Turner 548 HPRI pistons were made to similar thickness.”

The one thing you learn with engines is that nothing is set in stone. Both Tom Newton and Stan McDonald had dynos, and some of the cylinders that performed exceptionally well had really thin cylinder walls on one side and thick on the other. We are talking 1/8” or less on the thin side and 1/4”+ on the thick side. John worked with Hubbell a lot on dyno testing and probably found this out as well. No explanation for this phenomenon. When doing this type of work, you have to have a starting point, and a 3/16” cylinder wall was John’s measuring stick.

My second encounter with John was at DePue, Illinois when he showed up with his two-man DeSilva runabout with a Yamarude engine he had built. Jay Root was the driver and Bruce Summers was deck rider. This was the first time I had seen a starting stand built and operated by John with a single lever to launch the boat after the engine had started. I remember John filing on a prop most of a day prior to using it in a race.

Most of us who have bought from eBay were requested to rate the seller’s communication after the purchase. John’s communication skills were unchallenged. He must have answered every question from people phoning or sending him letters. Everyone who had asked John questions over the years probably had a large file of postcards and letters from John. He would never get an “A” in penmanship. One just adjusted to his style and eventually understood everything he was explaining in these cards and letters. This took a lot of practice and patience.

When we started to make pistons for the Speeditwin we wanted the same piston casting to work in the 4-60 engines. John took a casting and machined the piston pinhole difference, thickness needed for a two-ring piston. He sent me this casting that I still have in my shop.

When John made the crankshaft for the Yamarude, he sent me detailed photos during the process with written explanations on the back of each photo. Dated October 1968. Notes on photo back of the crank project copied as written by John.

Piston John sent me showing pin location for C-Service Speeditwin and 4-60 plus thickness for 2 ring piston, April 1988.

B&W photo of crankshaft steel. A good many crank billets would have to be made to forge as a rolling pin shape and reduce machine time as Hubbell and OMC did. End mains same for setup of throw blocks—no tapers or threads, etc., until after throws are machined. Crank’s center main should be cut first; not as here.

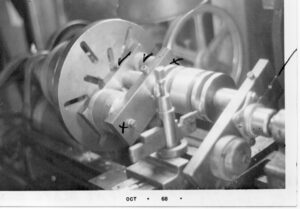

Crankshaft machining fixture. The accuracy of throw blocks will be accuracy of crank. Counterweights are of course needed. (X) Two studs hold double blocks. Tail stock throw block must be clamped tight, also must run a ball bearing. A Jacobs chuck arbor or similar must be ground straight on end so as a ball bearing must be mounted. Note: 4 lock screws at plate end – 2 shown.

Machining crank. Throw blocks need a rather large center drill hole so as to be able to dial in when attached to the faceplate. Dowel pins can also be used in a 13” lathe, the bigger the better. (x) Two studs hold double throw blocks together as assembly; other bolts and dowel pins are in backside of plate so can be kept as a unit.

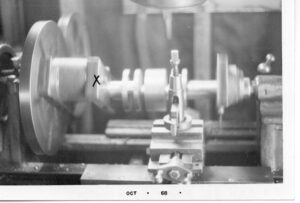

Turning crankshaft throws. Live center of lathe and throw blocks bored to 1/2 length of stroke so as to turn 2 crank pins of 4 cylinder +.010”. Crank is rotated 180°, then remaining 2 pins machined to +.010” +.003” -.000”. Five heavy extended cutters are needed L&R, center, and L&R radius. Note: Lock screw – 1 each side.

Turning crank. Cutting in center main on power feed and overhead drip oiler.

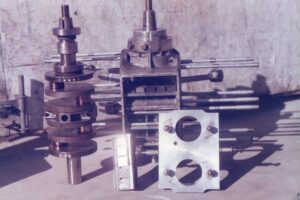

Partially finished crank. Throw sections removed after drilling using horizontal band saw. Throw cutout area can be trued up semi-finished by end mills; at same time shape crank pins to 8-sided. This can be done on a really big mill and rotary cutter. End mills are too small; deep cuts can cause breakage and lots of labor if one is to mill out the whole throw area.

Photo of procedure used in making this crank. Drill 3 holes 3/32” -1/8” smaller than throw width to allow for errors. Also, back away from crankpin to allow for saw errors.

Crank ready for crankcase. Two of a half-dozen 4-cylinder cranks I made. Thicker crank arms, V4 rod throw size to use their smaller rollers, and 2-piece retainers. After crank is machined +.010” on all bearing surfaces, these are covered with masking tape and end-glued over so as to stand 150°F temperature in copper plate process after copper plate tape is removed. The heat treat will only harden bare bearing surfaces 59-60 on C scale. Harden .020” – .050” deep.

Featured Articles