Jim Benson: Racer, Official, Author

January 31, 2024 - 2:22pm

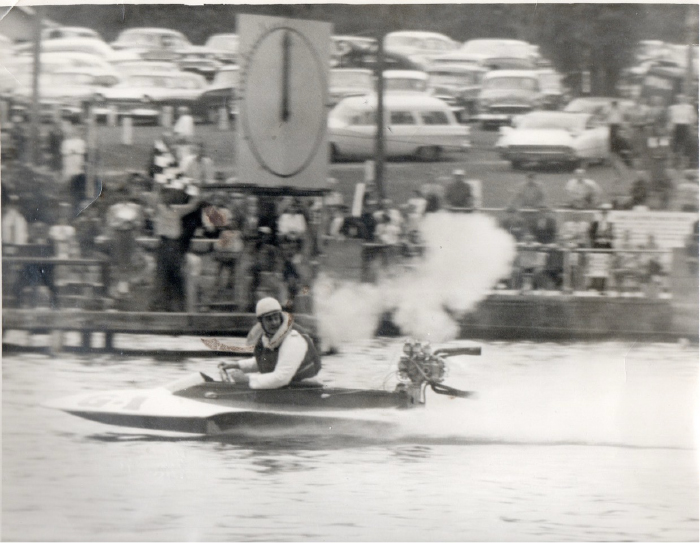

Jim Benson in the very fast 150 Hilton Hy-Per-Lube, the 1967 National High Point champion.

By Craig Fjarlie

Jim Benson was born into a Seattle racing family in 1943. His father, Al Benson, was a longtime outboard racer; his mother, Dorothy, was a scorekeeper; and Jim’s older brother, Donnie, also had a long career in racing. The family lived on Lake Washington when Jim was young. “Obviously, boating influenced us there,” Jim remembers. “My brother and I both got boats when we were five years old. I had my own little duck boat with a quarter-horse Elgin engine on it. My mother wouldn’t let us run out beyond the docks because we were only five years old. So, we’d run under the docks, back and forth. Eventually, we were old enough to start racing.”

The Benson racing family in 1953, with Donnie and Jim holding Al’s trophies from his Slough victory.

Al Benson fostered the JU class in the Northwest through Seattle Outboard Association. A number of young drivers who would gain recognition in boat racing were involved. “I think the first time that we all raced in was at Idlewood Park on Lake Sammamish,” Jim Benson recalls. “Bill Schumacher was first and I was second; Chuck Lyford was there too. Dad got all the neighbor kids, sold them boats, and got them enrolled in JU. Dad gave my trophy to one of our neighbor friends, so I don’t have that now.”

Benson continued racing outboards. “My first boat was a Jacobsen runabout. It was a combination AU and JU,” he says. “I was racing against Schumacher, my brother Donnie, Lyford, and of course, Ginny Lea Lyford. I did well, and eventually moved into the A Runabout class. We always wanted to run hydros, but we never had hydros back then. Ed Karelsen said anybody could drive a hydro, but it took a real man to drive a runabout. He was right. Those runabouts were the only boats we ever flipped.”

Benson won the 1958 Canadian Nationals at Harrison Hot Springs, taking first in both A Stock Hydro and A Stock Runabout. “I was probably only four feet tall and the trophies were almost as tall as I was.” Benson admits he had some close calls when he was competing with Mike Jones in local races. “We had some clashes and our fathers had words once in awhile, because I cut Mike off a few times and his dad didn’t like that. I don’t blame him, but back then, you could do pretty much anything you wanted. I didn’t do it on purpose, but I wanted to win when I was a little kid. I had that drive. My dad had a lot of drive, too, but not like I did.”

When Benson was in high school, he took time away from racing. “I was senior class president,” he says, “Then I went to the University of Washington as an engineering major. Got married, had kids, and couldn’t afford to keep going to school, so dropped out and went to work. I had various jobs from my boat racing. In fact, one of my jobs was for Harold Hilton, of Hilton Products. He had the Hilton Hy-Per-Lube Oil. He made alloy steel valves for the paper pulp mill industry. I was a draftsman then; I did all his drawings.”

Benson began driving inboard hydroplanes intermittently. “I had the opportunity to drive Jim Emil’s boat in the ‘62 Nationals. He called it Hydrostatic.” The boat was built by Ed Karelsen. “It was a 150,” Benson explains. “It was a pretty fast boat, but he always had problems with his engines and things. In fact, my brother drove it first. I drove it in the Nationals and only finished one heat. He was so mad he packed up and left because I couldn’t finish the second heat. When I went to work for Harold Hilton, he and I bought the boat from Emil. That’s when we called it Hilton Hy-Per-Lube. We bought it for $1,200; each of us put in $600. That was 1966; I only ran it a few times that year.”

The 150 hydro that Karelsen built had a number of unusual features. “Karelsen just built an oversized outboard,” Benson says. “I kneeled in it and had a hand throttle. It was about an 18-foot boat. We put air traps on it and did some other things to make it more like an outboard. I actually got it going from 80 or 90 to about 120. It was pretty fast for a 150. In ‘67, when I started going for points, I won almost every race.” Hilton Hy-Per-Lube was the 1967 National High Point champion in the 150 class. “It was amazing how fast it went out of the turns,” Benson continues. “It had kind of a crazy engine setup, with a vee-drive gearbox. The engine was way in the back. The shaft came out, went forward right behind my butt, and then into a little Collier gearbox, which was nice because I could change gear ratios according to the course. Then the vee-drive went out the back at a real low shaft angle, about four or five degrees. I had to race a ski boat propeller; it had the right shaft angle on it.” Benson describes the two-blade propeller. “It was kind of like an elephant ear propeller—a giant ear with lots of cup in it.” Benson looks back on 1967 with pride. “I was elected to the Marine Racing Hall of Fame at the end of the year. That was my glory year racing.”

Next, Benson moved into the 266 class. “I drove Ed Karelsen’s second cabover. Jerry Bangs was driving his Lauterbach boat. Bangs kept moving up classes; every time I’d move up a class, he’d move up a class. Finally, he went to the Unlimiteds. I didn’t want to go there because some of my friends were dying in the ‘60s. With a young family, I knew that wasn’t the thing to do.” Benson raced until 1971, when his career came to a sudden halt at a race on Seattle’s Green Lake. He won the first heat but had a serious accident in the second heat. “I got behind at the start and pushed too hard,” he explains. “I stuffed the boat and it threw me out, but I didn’t let go of the steering wheel. It ripped my helmet off. My head went through the deck five or six times. I had a really bad concussion. They couldn’t re-run it because it was too late; it was after 6:00 and they couldn’t run any more. We won the race, but I was in the hospital. Took me a year to recover. My doctor and my family decided it was time for me to quit racing.”

When Benson had recovered from his accident, he started a new job at Physio-Control. “I worked myself into an engineering position,” he says. “Took the rest of the courses I needed. I never got a degree, but I took enough courses to do the engineering job. I was kind of a renegade engineer and worked for them for 30 years.”

Going back to the time Benson was in school, he recalls the years he spent helping on the crews of Unlimited hydroplanes when his father was a driver. “My dad drove Miss Seattle and Miss Pay ‘N Save. Chuck Hickling took over when Dad broke his back while testing. Dad’s claim to fame was in the 1958 APBA Gold Cup. Miss Pay ‘N Save beat the Gale boat. There were two boats on a three-mile course. It was the most boring race in the world until the very end. I think Dad won by about three feet. That was the only time he won a big heat.”

In 1956 and 1957, when the season was over, the Miss Seattle team had a ride day when family members could go for a ride in the boat. Jim Benson’s father took him for a ride. “They had to take the seat out, then they put a plywood board across, so we were sitting on a piece of wood. He had his jacket and helmet on, and I had to have a jacket and helmet. It was noisy as hell, hot as hell, stinky, and very fast, very bouncy. I think we went 160 miles an hour. I got a little card that said I was a member of the 150 mile an hour club. I still have it in my wallet.” Benson actually earned his ride by helping on the crew. “They would grab me like a log and stuff me up into the sponson, because I was the smallest guy. I’d replace nuts and bolts all the time.”

In the 1962 Gold Cup, on Lake Washington, Miss Seattle Too, the former Miss Pay ‘N Save, crashed at the start of a heat. Driver Dallas Sartz was injured but survived. The boat was less fortunate—it was a total loss. There was one race left on the calendar, at Lake Tahoe. Miss Seattle was pulled out of mothballs and prepared for the regatta, to take the place of Miss Seattle Too. Sartz was still recovering from his injuries, so Al Benson agreed to drive. Miss Seattle was an also-ran; the new Miss Bardahl won the regatta. When the race was over, Jim Benson and Dixon “Dax” Smith, a crewmember on Miss Bardahl, both needed to return to Seattle to attend classes at the University of Washington. “Harrah’s Club took us in a Silver Cloud Rolls-Royce to the Reno airport,” Benson remembers. “That was kind of fun.”

In 1963, Milo and Glen Stoen had a new boat, Miss Exide, and sponsor to replace Miss Seattle Too. “Glen Stoen was my dad’s best friend,” Benson says. “He always financed all my dad’s boating stuff and everything he did. I traveled the whole circuit in ‘63; drove the truck. My dad was the manager of the boat at the time. We went everywhere, to all the races. Started with the Karelsen boat, and Mira Slovak drove the first few races. It was a very fast boat, very fast engine, but they put the wrong shaft angle in there. The thing tended to nosedive a lot. At Coeur d’Alene, Muncey and Slovak were tied for points in the final heat. Slovak just pushed it a little too hard.” Miss Exide stuffed and crashed; Slovak was injured; the boat was destroyed. The Stoen Brothers replaced it with the former Wahoo, which had last raced in 1960.

Benson knew many of the colorful characters who competed in the Unlimited category. “I remember when Bob Gilliam had the Fascination next to us in the Seafair pits. I was about 50 feet from the boat, talking to somebody. Gilliam was starting up his engine and over-revving it. The damn thing blew up and the supercharger pieces landed right at my feet—the big chunks were about a foot in diameter. That was kind of crazy. I did work with Bob Gilliam, because when I worked with Harold Hilton, he was also sponsoring Gilliam. I had to get him up out of bed half the time. He was always partying the night before the race, and had girlfriends. He never would get up on time and I’d have to get him to the race. They never had all the equipment they needed, or they hooked things up wrong. One time they hooked up the water lines to the fuel lines and the fuel lines to the water lines. The whole engine filled up with fuel. I had to borrow a carburetor from Budweiser. They never would have loaned it to Gilliam, but I knew all the people. They were all guys that had worked on engines for my dad and we’d borrow a carburetor from them. I had to keep Gilliam going for at least half a year. Gilliam also painted my Hilton Hy-Per-Lube the poppy red color. He was a nice guy, but he was such a character. In that junkyard he had in Bothell, the old Miss Seattle was sitting out there for years, along with all that junk. He was real proud of all that junk. People would go out there and get needed parts from him. I was surprised when I did that Slough race spreadsheet, that he actually raced in the Slough one year.”

Following the accident that ended his driving career, Benson began working in an official capacity. “Lin Ivey, who was the starter for the Unlimited races on the West Coast, got me involved in helping him,” Benson explains. “When I quit racing, I became an official. Eventually, when Lin passed away, I took over as the chief starter for the West Coast Unlimited races. We replaced the starting mechanism that was made from slot machine parts that ran the clock and everything. I designed a computerized system to run all that. We were always screwing up trying to count down backwards. Sometimes we had to start over and that really upset everybody. I had to do something to fix that. I eventually became the chief timer. I designed the first efficient computerized timing system with a guy from Boeing. He did all the software on it. I did that for about 15 years, then got fed up with the politics.” Benson also did timing for inboard and outboard record races in Region 10. “I had a little Macintosh and I’d bring that and run it on the generator. I had a little program. All I’d do is put in the seconds and it would automatically do all the scoring, so we knew what each lap speed was, and we could alert people when they were under the record. I really enjoyed that; and my wife, Carolyn, would come out and help me.”

In 2003, Benson retired from Physio-Control. “We decided that we needed to dry out, so we moved to Arizona. We thought warm weather would be better for our aching bones.” In the process of moving, Benson had to make room for a huge collection of hydroplane records and memorabilia that he wanted to take to Arizona. “My dad had hundreds and hundreds of photographs from Bob Carver, Bob Miller, and all the press photographers, and my mother had saved all of the newspaper articles. I had this collection of boat racing memorabilia that went from the early outboards to my brother’s and my outboard racing, to our limited racing, to my dad’s Unlimited racing. I still have all that stuff. My wife kept telling me, ‘You’ve got all these boxes of boat racing stuff—you either have to do something with it or get rid of it.’ We were living in Arizona at the time. I just procrastinated over the years. It’s all still down there.”

The Sammamish Slough race was a fixture on Seattle Outboard Association’s calendar from 1934 through 1976. The marathon event was nicknamed, “The crookedest race in the world.” The Slough connects the north end of Lake Washington with Lake Sammamish, which lies east of Bellevue. The Benson family had a long connection to the Slough marathon. Al Benson was the overall winner three times, and both Jim and Donnie competed in the race. The event was discontinued after the 1976 race when a spectator was hit by a boat, which resulted in a lawsuit.

Dave Culley, a longtime outboard racer and Unlimited hydroplane crew chief, won the Slough race three times in a row. In 2013, his daughter-in-law Amberly began talking to Donnie Benson and other members of Seattle Outboard Association about putting together an annual exhibition event as a memorial to the Slough races. Then, one day, she called Jim Benson. “I think my brother gave her my phone number,” he begins, as he relays the story. “She started talking to me about the Slough races and I started talking to her about what I did. Pretty soon we’re almost like brother and sister, because we had so much in common. She’s very similar to me—very hyper, into details. She finally said, ‘You’re the missing link to my program here.’ She helped persuade me that I needed to write something. The light just turned on. Yeah, the Slough race was the thing, because I had all this history.”

Beginning in 2014, the Kenmore Cup Slough exhibition took place on a spring day. Drivers went a half-mile up the Slough, turned around and returned to the pit area. Former APBA President Rick Sandstrom was the referee. Local merchants and the City of Kenmore were supportive, and the annual event has been held ever since, except for a break during the Covid period.

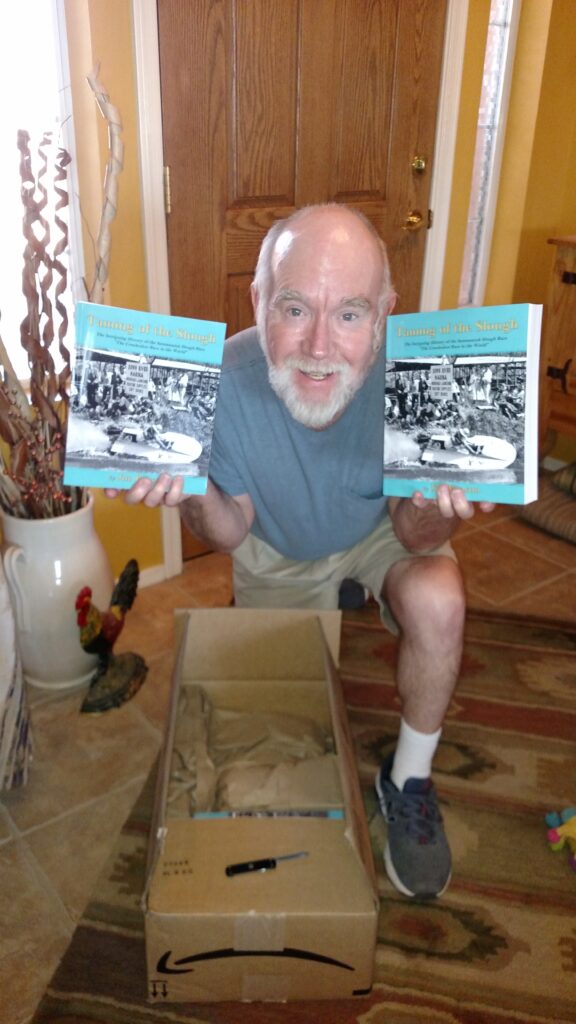

Meanwhile, Benson began researching and writing a book about the Slough races. In addition to his own memorabilia, he used records from the Seattle Times newspaper, the Seattle Public Library, and the Museum of History and Industry. Benson spent four years on the project. The 540-page book, Taming of the Slough, was published in August, 2018. In addition to details about each race, Benson covers early history of the area and profiles major race participants, including Elgin Gates, Robert Waite, Al Benson, Billy Schumacher, Chuck Lyford, Ginny Lea Lyford, Bill Muncey, Howard Anderson, Chip Hanauer, Janis Lee, and Dave Culley. He also devotes a chapter to photographer Bob Carver. The book is available through Amazon, and readers in the Greater Seattle area can purchase it at the Hydroplane and Raceboat Museum in Kent, Washington.

Jim Benson has spent a lifetime involved with boat racing. As a racer, official, and writer, he has made major contributions to the sport he loves. His book preserves a major part of the history of outboard racing in the Pacific Northwest, and for that, we offer our thanks.

Author, author! Jim Benson shows off the first copies of his book, Taming of the Slough.

Featured Articles