A Boatbuilder Shares His Memories – Part 3

August 18, 2022 - 9:22pm

Ed Karelsen listens to Don Benson. Photo courtesy of Jim Benson

In the first two parts of our interview with Ed Karelsen, he explained how he became involved with boat racing and eventually began building boats. He studied engineering at the University of Washington. Karelsen raced outboards and worked for Al Benson. He put his skill to use building outboards, inboards, and Unlimited hydroplanes. In the final installment of the interview, Karelsen recalls Unlimiteds he built for Bernie Little, Shirley McDonald, and Fred Leland, and shares stories about some of the people he met along the way. The interview was conducted by Craig Fjarlie on January 31, 2012.

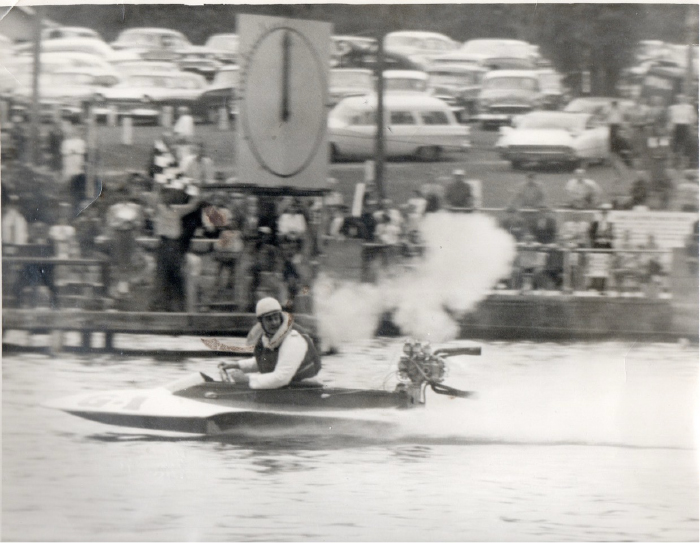

Bob Carver’s photo of Jerry Bangs ejecting from Champagne Lady.

We were talking about Jerry Bangs’s crash in an Unlimited. Do you have any comments about what happened?

After his accident they had me look at it, along with (Ron) Jones and (Don) Kelson. They both wanted to change the sponsons. I said, “No, it’s not the sponsons, it’s the shaft angle.” Well, they never changed that—it’s too much work—but it’s the most critical part of the whole damn thing. If an outboard is kicked out too far, you blow it over. You probably should lower it. They don’t understand that.

You built a new Miss Bardahl in 1967, then Miss Budweiser in 1968.

Bill Harrah’s private secretary happened to be a gal I knew. She had gone out with my brother in high school. She won $1,000 from Harrah. She’d travel with him to the boat races for a year when I built the Bardahl. In Florida, he was telling her about this new Staudacher that Ole (Bardahl) had bought. She told Harrah, “It’s not a Staudacher, it’s a Karelsen.” Harrah says, “No, no, no, I’ve never heard of that one. I’ll bet you $1,000.” She says, “OK, I’ll take that bet.” Harrah walks down there, and right across the back it says “Karelsen.” He says, “When you get back to work you can write yourself a check for $1,000.” (Laughter.)

Photo by Randy Hall of the Karelsen-built Miss Budweiser at Seattle, 1971. That’s Dean Chenoweth standing on the deck.

Were there any significant differences between the Bardahl and the Budweiser?

An exact duplicate, except the crew put the shaft log in. The whole shaft, all the installation, the engine and shaft, I had all the markings on the engine rails where the centerline of the crankshaft should be. They didn’t miss it by far. I told Bernie Little, “I usually go with the boat the first year, the first couple of races, to make sure everything’s OK.” “Aw, we don’t need you,” he said. Well, they got to Detroit, two races in, all they do is blow up motors. He was plowing it, on its nose plowing. In order to keep it accelerating, they were pulling 125 inches of manifold pressure. The red line, I’d guess, was at 80. So, they’d blow the engines up. Little called me at 3:00 in the morning: “Get your ass here.” I flew out to Detroit. It was windy as hell; they couldn’t do any testing. Both boats were sitting there side-by-side, the Budweiser and the Bardahl. Roy Duby was there. That was the first time I’d met him. He wanted to help me measure everything up. I said, “Everything’s identical.” We couldn’t figure anything. The only difference in the two boats was the rudder on the Budweiser was an inch wider than the Bardahl because George McKernan wanted it. Duby said, “Hell, an inch on the rudder ain’t gonna make a hill of beans. And anyway, it’s plowing and blowing up engines. I’m one of the buddies that knows everything about it and they’re all telling Bernie different things. They went to shim the sponsons, they did all kinds of stuff and that didn’t work.” I think it was Friday night and they were canceling the race because the wind was blowing. I was walking away talking to Roy Duby. We were about halfway down the pits and he was looking back at the boats, he says, “Look at the carburetors.” I couldn’t even see the carburetors. Didn’t know what he was talking about. He says, “C’mon.” We go back there. The engine in the Bardahl was down here and the Budweiser was up here (gestures). The shaft’s two inches deeper. The boats were identical, but the carburetor on the Budweiser was two inches higher off the deck than the Bardahl. “Oh, the shaft angle’s wrong.” And so, “Bernie,” I said, “the shaft angle’s wrong. We gotta change it. I’ll haul the boat to Staudacher. You can have George and the crew go home and build motors and I’ll meet you in Pasco.” He says, “Oh, hell, that can’t be it.” I said, “Hey, Bernie, I built the damn thing. I think I know what’s wrong. I’m volunteering to fix it. If you don’t want me to do that I’ll leave and you’re not paying me for being here—you’re just paying my expenses.” When we got there, we measured everything. You know what 3/8 is?

Not exactly sure.

3/8 of a degree, 2/8 of a degree. In minutes, it’s about 28 minutes, that’s all.

That was enough.

You wouldn’t think so. In an outboard, you want to go more, so you kick ‘em out. We didn’t change the strut or anything; we just took everything out. All we did was drop the strut down and it changed everything. Took the shaft log out, put the strut back and dropped it 2/8 of a degree, which was two inches. Everybody said, “Aw, hell, it ain’t gonna work.” Well, we went to Pasco and took second, and then three years National Champion. I still talk to the crew. They say, “That didn’t do it.” Ha, ha. “You guys don’t understand it.” The first thing they wanted to do was to tear the sponsons off it.

When Bernie bought the boat from me I said, “You ought to buy some propellers.” He said, “I already got two of ‘em.” He ended up, I think, with 25 of them that year. I said, “There’s a big difference in propellers.” That’s the first thing I look at, and cg (center of gravity). I tell the guys you don’t have to be perfect on cg, but if you don’t know your cg, you should put a 4 x 4 underneath there and let it sit on the air traps. You don’t need a knife edge—just a 4 x 4. You put the driver and everything in there, and fuel, or something equivalent, and just balance it. A teeter-totter. The thing you do there, 3-½ inches, put it in the center there. That’s the cg. Whether you’re off an inch or not isn’t a hill of beans. You’ve got a 2,000 pound Merlin sitting in there with a gear box. You can move it four inches either way and it won’t get you much, but if you take something out of the rear and put it in front, it’ll really change.

Karelsen with a boat he knows well, at the Hydroplane and Raceboat Museum.

It’s funny, after George McKernan quit the Budweiser and Tommy Frankhouser took over, well, all the nitrous bottles were behind the driver’s seat. There were three of ‘em, and they were big bottles. The crew was getting tired of taking the seat out and crawling under there; it was hard work. So he took all the bottles out and put ‘em up front by the carburetor. George called me and said, “Tommy called me and says the boat’s running lousy and I can’t figure out what’s wrong with it.” I was out in the north end then. “Come by here and let’s go down and see what they did.” The first thing George did was crawl up on the front deck and says, “What the hell are the nitrous bottles doing up here?” Tommy says, “Well, it’s easier to work on.” George says, “I didn’t put ‘em back behind the driver’s seat to make your life miserable. That’s where it goes to make the balance right.” You know, he took all the tech stuff out before anybody else did and put everything where he wanted it. They put ‘em back where they belong and it was fine again. The simple things they missed.

Photo by Randy Hall of the Karelsen-built Notre Dame, taken at Seattle, 1971.

You built a Notre Dame for Shirley M. McDonald. She didn’t get a win with it.

That was funny. I built a boat for her and she had 15 crew chiefs and no Indians. You know, nice bunch of guys, they didn’t know what they were doing. They had a drunk for a crew chief. Nice drunk, I enjoy a drink, too, but I remember Fraser (Shirley’s husband – Ed.) would come to the pits every morning, he’d say, “Crew chief can’t make it, he’s got whiskey flu,” or something. It was ridiculous. Anyway, the engines they built had too much clearance. They didn’t take the time like the Budweiser crew would do to get the clearances down on the blower so they made horsepower. Leif Borgersen would get on the nitrous and he couldn’t finish the heat. You could tell ‘cause when the engine would quit and Leif would finally get started again, a big, black cloud came out of it ‘cause it richens up. If there’s no nitrous there, it don’t work. We broke every qualifying record at every racecourse that year and never won a boat race. She asked me how she could win a boat race. I told her, “Well, you have to fire everybody and find a guy who knows what he’s doing.” At that time I would have said George McKernan, but George decided he wanted to get a job with the Stoen Brothers until retirement. I said, “Your driver’s a nice guy but he’s had no experience.” I mean, in all the pictures you can see who’s outside and farthest back, Leif, and he’s trying to go to the infield. Dean Chenoweth got a kick out of it ‘cause he’d keep him on his hip. The boat never finished heats. When we’d go to San Diego, the crew were such prima donnas and fighting with each other. They were such a big crew, they had Vacation Village there, and she gave every one of ‘em their own cabana.

Oh, wow.

She thought she’d make ‘em all happy. But they still weren’t happy. They always did something wrong. They didn’t do their homework at home when they were supposed to be doing it, and the boat always quit. So, we didn’t win enough, never made all the heats. I think the last one was when they hooked up the oil line to the water and they didn’t make the final heat. They didn’t have enough points to get in the final. She asked me what to do. I said, “First take the priest and send him home back to Notre Dame, and fire the whole crew and get somebody who knows what they’re doing.” And I said, “Get a good driver. Take the cloverleaf off the tail and put a swastika on it. We’ll have everybody pissed off but we’ll win races. You won’t ever get the sportsmanship trophy any more, but you gotta take that down.” “Oh, I can’t do that.” I’m just kidding. She wanted me to take the boat over but I really didn’t figure I was qualified to do that. You know, she was worth something like $95 million at the time; she could’ve done anything.

She was nice. She was about my age—two years older. She was a nice lady but she didn’t understand people, they scared her. She went on a date, she was very thin, if a guy gave her a Scotch, she wanted a hot dog. (Laughter.) But there’s no reason she shouldn’t have won. Just get the right people. She thought she had ‘em, two crews of guys. The old crew, Wes Keisling and Mike Welsch and a couple others, did know somewhat what they were doing and tried to solve it, but the two crews were fighting each other. They didn’t want to stay with the boat for only half a season; they were going to leave it for the other crew. They were all nice guys but they didn’t know what they were doing. They kept thinking that Unlimiteds are different. They’re not. It’s the same old thing. No different than an F Hydro. The Bardahl, basically, was a copy of the Jones they had before. The only thing they did, they let me do what I wanted to do. The side dimensions are the same, had the same break in the bottom and the outside dimensions. But I changed all the nontrips on it. And I do one thing different than everybody in the country. I twist all my boats. There was a whole inch twist in the Bardahl.

You were going to build a boat for Bill Harrah, but he abandoned racing before the boat was finished.

I wanted to try an idea: make all the frames out of aluminum. I started that with Harrah’s Club, a whole aluminum boat. He owned all these Rolls-Royce Griffons. The only thing wrong was that the boats were too heavy with the Griffons in them. He ordered the boat, so I spent the first month down there laying everything out. They had most of the frames built. They were split tubing, welded together. Then the deck. They were like an airplane. They had an aluminum piece of angle on each side. The whole bottom was going to be corrugated aluminum. They were going to make their own. You put one piece in there across, 30-thousandths aluminum, then they had this machine to corrugate it, an angle going off here (gestures), and an angle going off, like a corrugated roof. They had some special aircraft pop rivets they were going to use and pop rivet the first part to the frame and the other ones to the battens and everything, and then you pop rivet the bottom. They tested everything and it was great. They were getting ready to assemble everything and I flew home for Christmas. When I was home, Harry Volpi called me the day after Christmas, says, “The whole thing’s been canceled.” I said, “You’re kidding. Why?” He sent my plans back and the whole thing, and said good-bye. I couldn’t find what happened. Well, the driver was too cozy with Harrah’s wife. I had to call the secretary about this and she thought it was Mira Slovak. He said, “Hell no, I hadn’t been around for two years.” So it must’ve been Jim McCormick, ‘cause he was the driver then. Anyway, that was the only boat I was ever screwed out of. He canceled everything. He got rid of all the engines, sold everything to Bernie Little for almost nothin’. Bernie bought it all. When they brought the stuff back to the shop down at Boeing Field, Bernie said, “Just put the engines away. We’ll probably need ‘em one of these days.” They finally got Jones to build the Griffon boat, and hell, it was unbeatable. I remember talking to Bill Muncey before he got killed and he said, “I‘m going faster than I’ve ever been going. I’m turning the damn Merlin 4,000. But I can hear Chenoweth coming in that Griffon boat.” Muncey’s the one guy who said he wouldn’t kill himself in the boat, but he blew it over down there (in Acapulco) trying to stay ahead of the Griffon. Chenoweth stuck it a couple times, too, until it killed him. Now they got the capsules. They’re still deadly, but before, on a 1 to 10 scale, they were about a 2; now they’re about 9-½. That’s why I say there’s no reason we can’t have capsules in outboards.

You built a piston-powered Unlimited for Fred Leland—one of the last Merlin boats. It didn’t really work too well.

A year’s project, and we didn’t change too much. One mistake was that we had all aluminum freight. Fred went and bought two other boats because they were heat-treated. I said, “Fred, you have to get the heat-treated ones; these aren’t going to hold.” Well, the frames were all breaking up inside of it. You know, he couldn’t fix ‘em. He could call somebody and run it until it fell apart. Let’s see, that friend of his, what was his name? He used to drive a boat back east, used to drive standing up. Had a 7-Litre that never made a race, too. Anyway, he had about 20 propellers, and gave ‘em all to Fred. Fred knew a guy who was a prop checker. Fred said, “Pick out the good ones.” He says, “There’s not a good one in there, they’re all junk.” Leland said, “Well, pick out the best one.” I said, “Fred, there is no best one, they won’t work.” He put ‘em on anyway. Fred was the first driver. It flung him out. He didn’t care for that any more. He hired Scott Pierce. We were down at Seafair, where Pierce bent the steering wheel out of it, real bad. Couldn’t steer it. Anyway, “Pierce did that on purpose.” “No, Fred, the damn props are too big.” I said, “They’re blowing your engines up, they’re pulling the wrong direction and you can’t steer it.” So he went and borrowed a Record prop from Jim Lucero. They put it on the boat and it worked fine. Lucero says, “If you lose it, $3 grand.” They never did have any props on it to run, and you can’t tell Fred anything. He had a copy of the Champagne Lady. It didn’t work, either. He put the shaft in too steep. Fred’s a great guy, but the only reason he did so well was that Dave Villwock was doing all of it. I’d go to lunch with him quite often and he’d tell me what Villwock wanted to do and I’d say, “That sounds about right; do it.” As soon as Villwock left, everything went to hell again.

Leland is a genius on a lot of things, but he’s kind of like the mad scientist. He’s got a lot of good ideas and he can do it, but the stuff doesn’t hold up. He was building engines for a three-engine Unlimited. I said, “Fred, why are you wasting all that time? It’s not simple. You wouldn’t put three Chevrolets in your helicopter.” (Laughs.) After he’d worked with the turbine, I mean, there is so much power there it’s ridiculous. Simple. The thing is, the Merlin is 3,000 horsepower. The turbines have 3,000 horsepower. You run the Merlins 2.6 overdrive, so you’re lucky you have 500 horsepower at the prop. You take the turbine, the N2 is turning 18,000 to 20,000 on a 60% underdrive. You’re running around in duels in low gear. You’re still turning the prop faster than it should be and it’s more efficient. About 12,000 rpm, I would say, they are starting to cavitate, or like the prop on an airplane hitting the sound barrier. You hear it on those aerobatic planes—they go pop, pop, pop when they come down. They’re breaking the sound barrier. Well, the props do that in water, the same way. I remember we tested the Bardahl with a bunch of different props and different pitches. They all ran the same. I measured the props and all of ‘em had the same leading edge pitch: 16 inches. Consequently, no way in hell you can compete with a turbine when it’s got 5,000 horsepower at the prop and you ain’t got 500. I argued that with Dave Culley, too. We’ll solve that. Go to halfway, it’s way beyond. They think piston engines can do it.

Ed Cooper back east, he’s doing pretty well with his boat. The boat has to make weight and he’s lucky he can run any way he wants. He still has to go up there against a good-running turbine and beat ‘em to the first turn. If he does, they go around him on the outside. It’s just like Grayson Jones. He did a very simple thing no one else did. All these guys go around the turn, their Chevys, 350 Chevy over 7,200 ‘cause that’s what makes the most power on the dyno. So, they’re all running 22- and 20-inch props. I was talking to him one day on the phone about his engines. He wouldn’t tell me anything. I asked him, “What size prop you running?” Long pause, “20 inches.” You’re going around in second gear and they’re all running in high. It’s like a quarter mile track for midgets. Real simple. No wonder Ken Muscatel beat him to the first turn. He’d go around the outside because he’s got more horsepower and he’s gone. If it’s a long enough straightaway, Muscatel would’ve gone around him. It’s so simple. All you need is 8,500 in the first turn and the race is over with. If a guy catches you after that and goes around the outside, there isn’t much you can do anyway, unless you’re turning 9,500. But there’s no reason you can’t build a 350 that’ll turn 8,500.

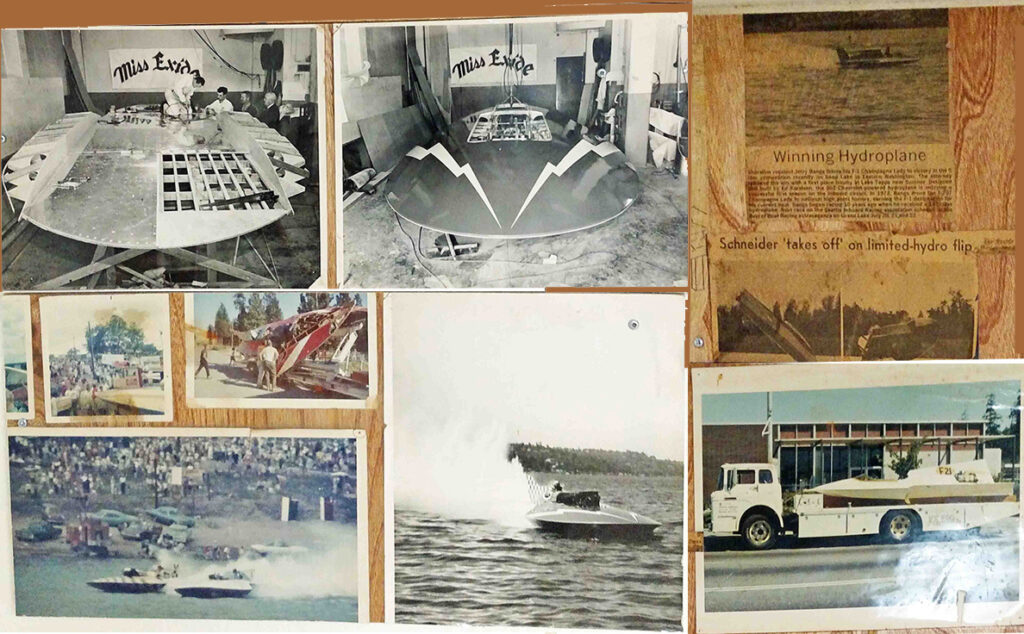

Some of the memories on Karelsen’s shop wall.

Just to wrap up, you’ve built outboards, inboards, Unlimiteds, and OPCs. Do you have a favorite category or type of boat that you built that you like?

I’m an old outboarder, but still, it’s all the same to me.

All boat racing.

It’s all boat racing and I liked all the classes. The tunnel hulls were fun and I love winning. You know, it’s much easier to win than it is to lose. I get a kick out of things people do.

Thank you for your time.

Oh, I’m glad to do it, talkin’ about all that old stuff.

Editor’s note: Ed Karelsen passed away on December 29, 2018.

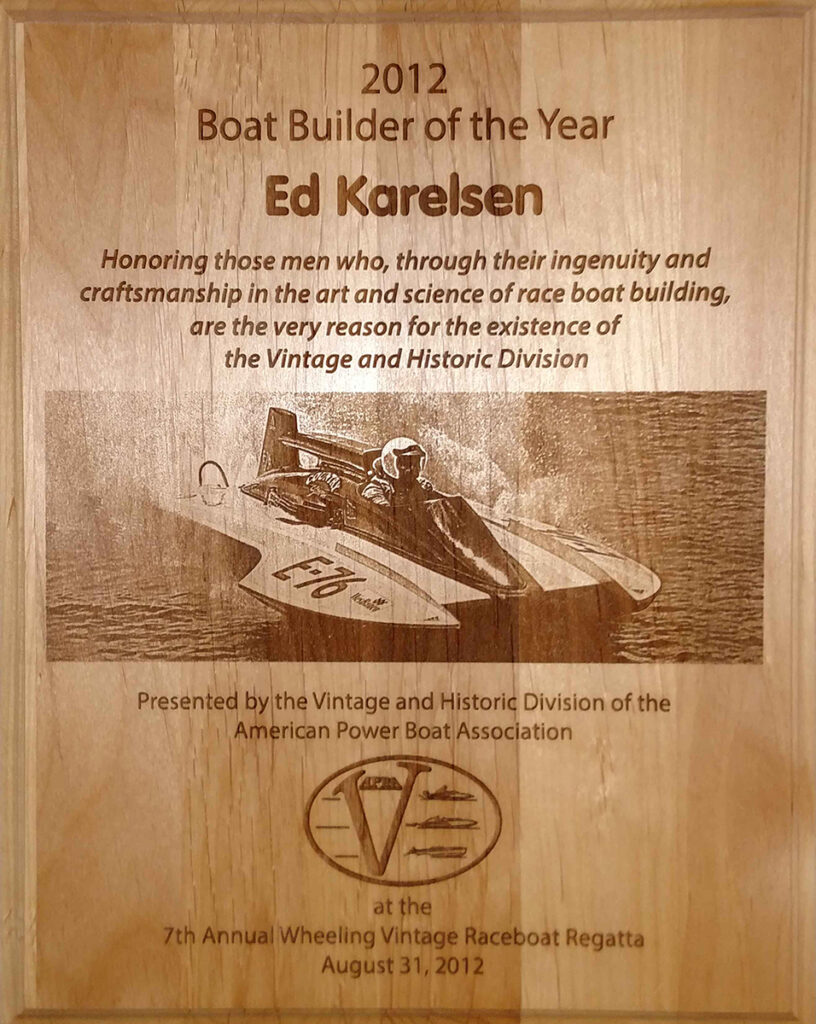

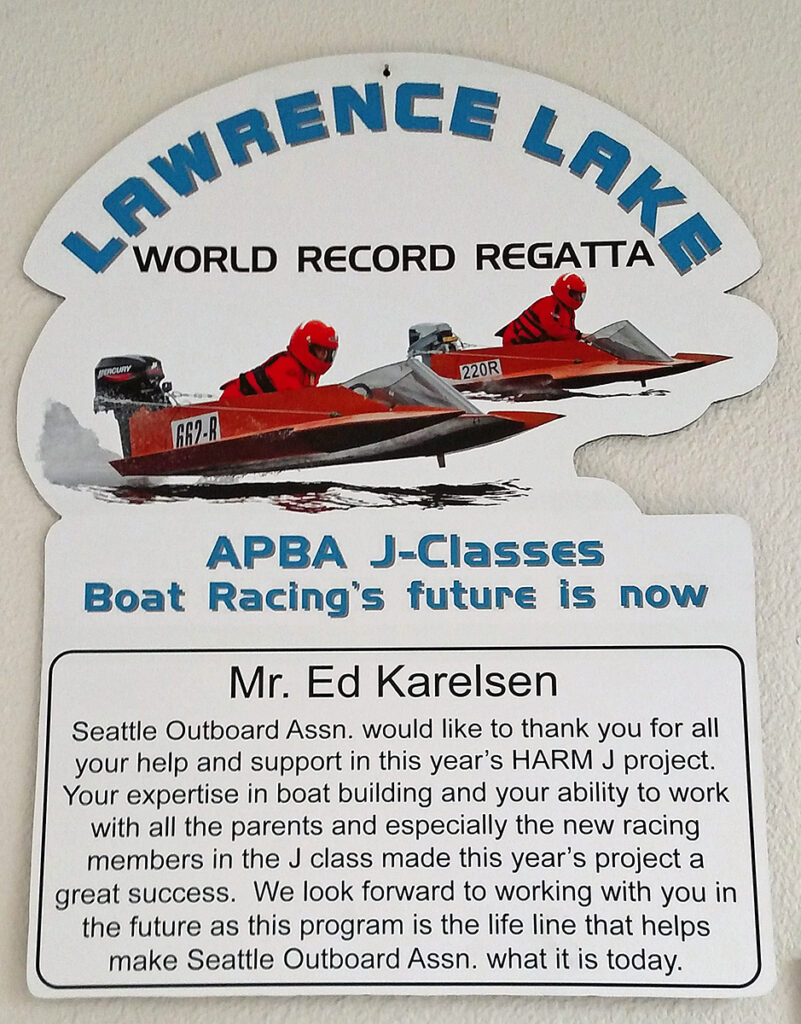

A FEW OF ED KARELSEN’S AWARDS

Ed’s 2001 APBA Honor Squadron certificate.

Ed’s 2012 Boat Builder of the Year Award.

This may be the award that meant the most to Ed Karelsen. The certificate from Seattle Outboard Association honors a major part of Ed’s lasting legacy- his contributions to young novice J Hydro drivers. He donated countless hours, providing hydro plans, mentoring young drivers, and helping the kids and their parents build their own raceboats at the Hydroplane And Raceboat Museum. It was one of Ed’s proudest achievements- helping future young drivers in the Seattle Outboard Association and the American Power Boat Association.

SOA and J Class representatives presented Ed the appreciation award at one of the Club meetings.

Featured Articles