Bob Wartinger: Remembering a Record Run

February 24, 2022 - 9:33pm

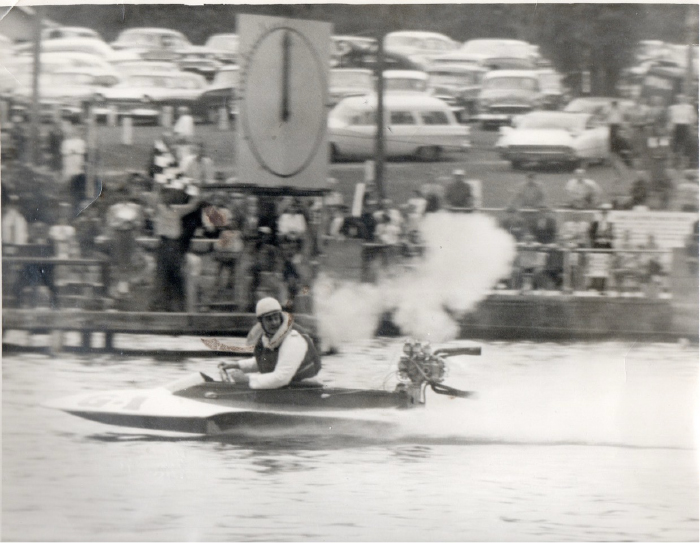

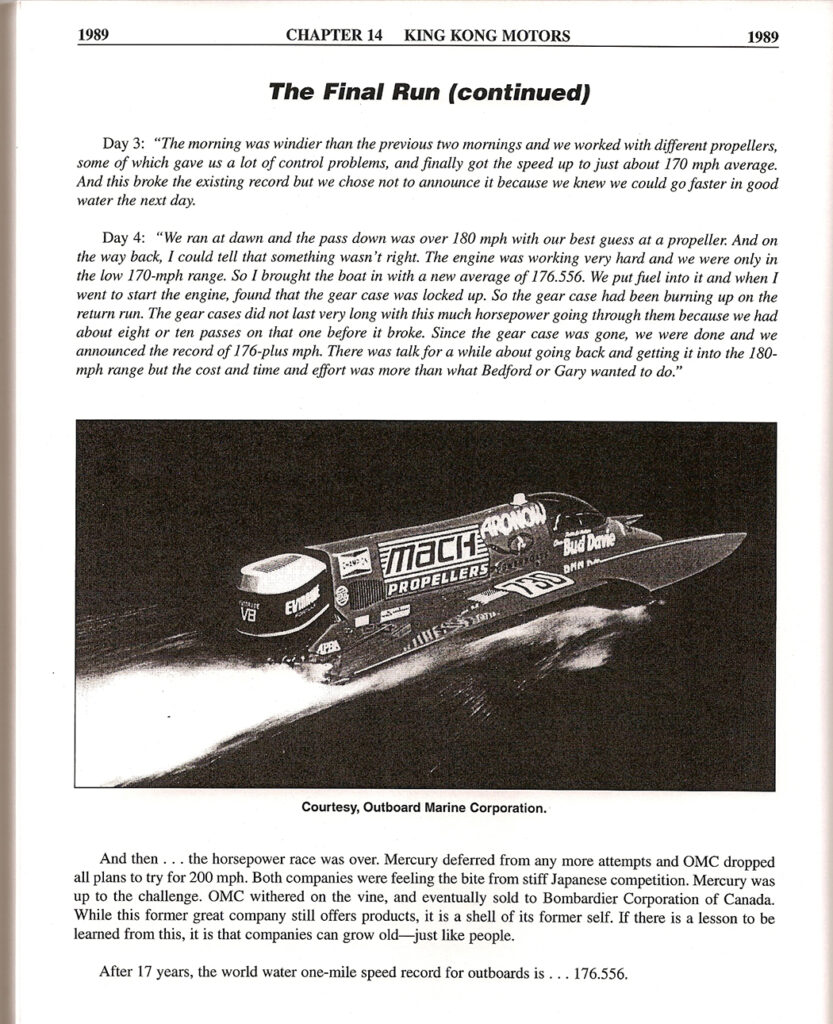

1989: Bob Wartinger drove this Ed Karelsen-built hydroplane to a World Record on the Colorado River in Parker, Arizona.

By Craig Fjarlie

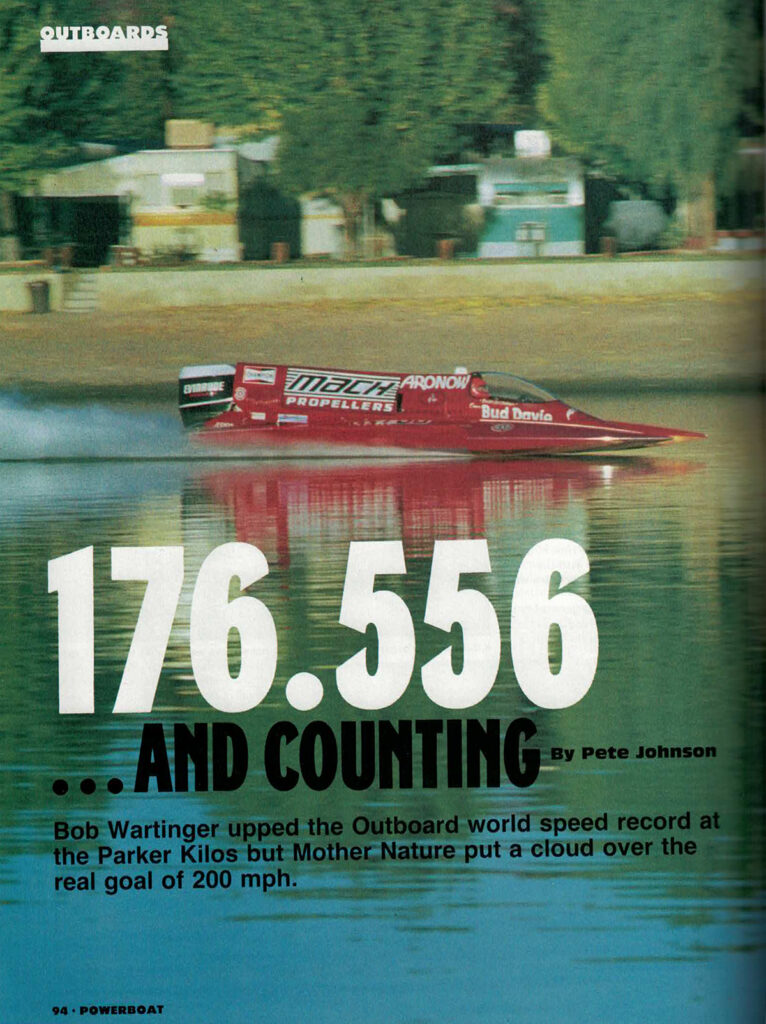

Bob Wartinger has been involved with outboard racing for more than 60 years. During his long affiliation with fast boats he has set a number of records, both straightaway and closed course marks. His most dramatic accomplishment took place in 1989 at Parker, Arizona, when he drove an outboard-powered hydroplane to a kilometer record of 176.556 mph.

An account of the 1989 run from King Kong Motors and POWERBOAT Magazine.

Wartinger made his first attempt at outboard racing in 1961 when he entered the famous Sammamish Slough marathon race near Seattle. “I had an old Scott-Atwater engine and they put me in A class,” he remembers. “I didn’t make it more than a quarter of a mile. But I tried in ’61 and ’62. Then, in ’63, I started running a Novice race and went through the Seattle Outboard Association school.”

When asked how he was selected to drive the boat in the straightaway record attempt, he digresses for a few minutes to relay a story. “They had a monkey in the boat and he’s all wired up, gauges and a heart rate monitor, blood pressure, and all that. He got up to 120 mph and his heart rate got too high. The monkey said, ‘I quit,’ and I was next in line.”

Once the laughter from the “story” subsides, Wartinger becomes more serious. “Actually, Ed Karelsen called me. He built the straightaway boat. It was the second one in a series,” Wartinger explains. “He said, ‘Bedford Davie wants to set the outboard record with a turbocharged Mercury.’ So I said, ‘Okay.’ We went to Modesto to try to run and set a record. We had a series of engines and we tested and ran but we had engine trouble. It wasn’t all worked out yet.”

Bedford Davie suggested to Wartinger that he resign from his position as an engineer at the Boeing Company and work full time on the boat. “I didn’t want to leave Boeing and my career,” Wartinger admits. “So, Bedford and Karelsen talked and they turned the project over to Bobby Hering.”

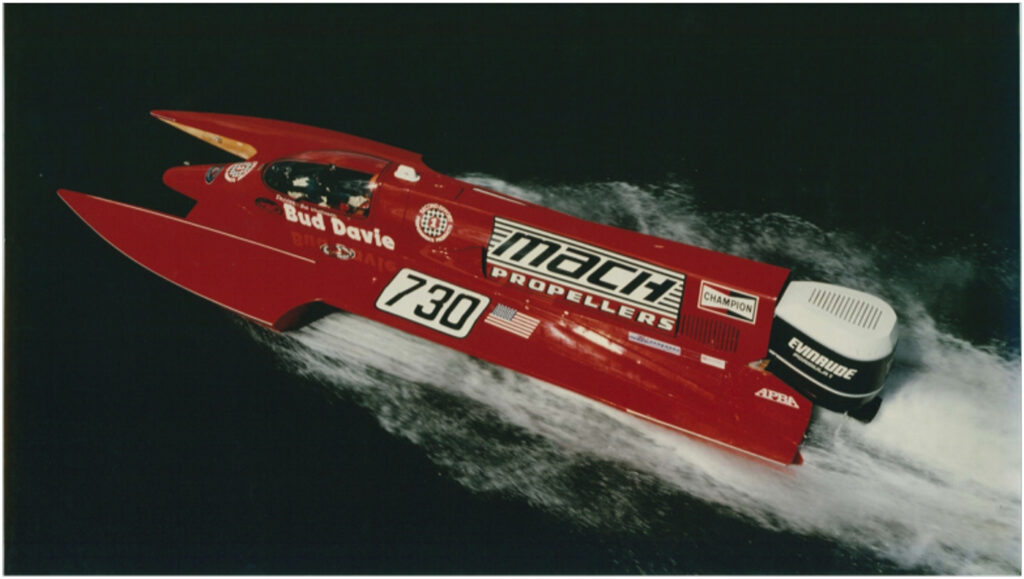

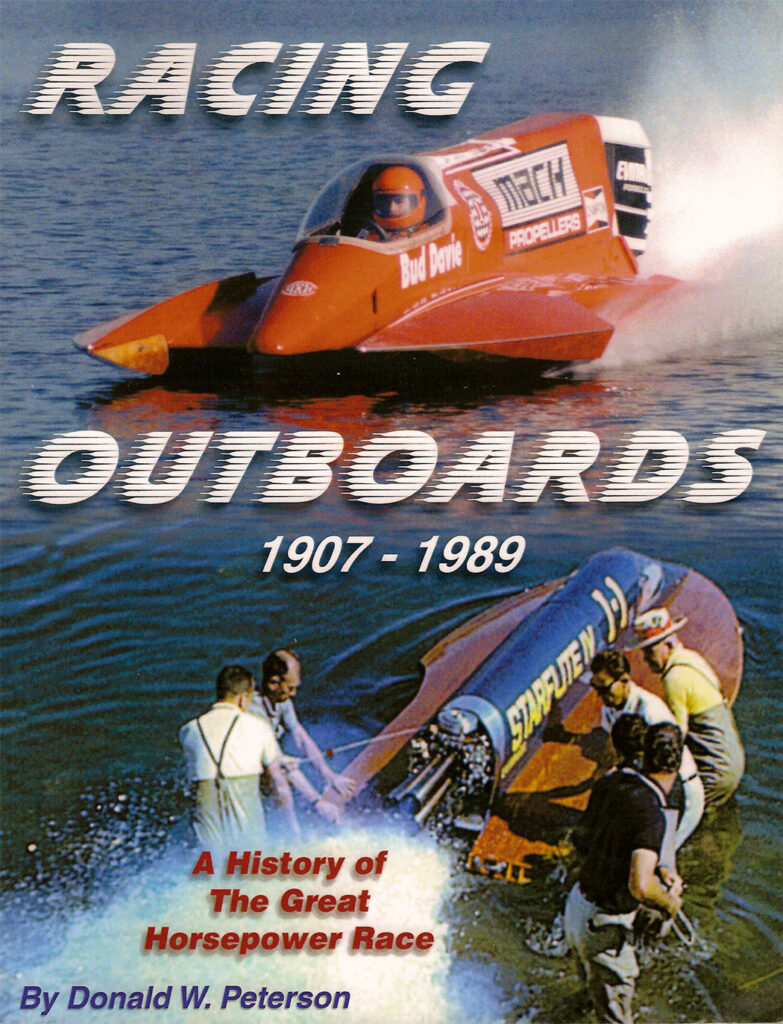

The record-setting boat is featured on the cover of Donald W. Peterson’s book RACING OUTBOARDS 1907-1989: A History of the Great Horsepower Race.

Bedford “Bud” Davie had raced outboards on the east coast in the late 1920s and early ‘30s. He was usually dressed in white when he raced. “He now was very interested in both the Antique classes and in setting the record,” Wartinger recalls. “Then Gary Garbrecht saw the boat and Hering in Florida at a record trial and he said, ‘Let’s put an OMC on it, V-8.’ So they tested and eventually went to Parker, Arizona, and Hering set the record. They ran two records within about 20 minutes. I think they ran OZ – a UIM-type record – and an unlimited outboard record, so to speak. Same boat I drove.”

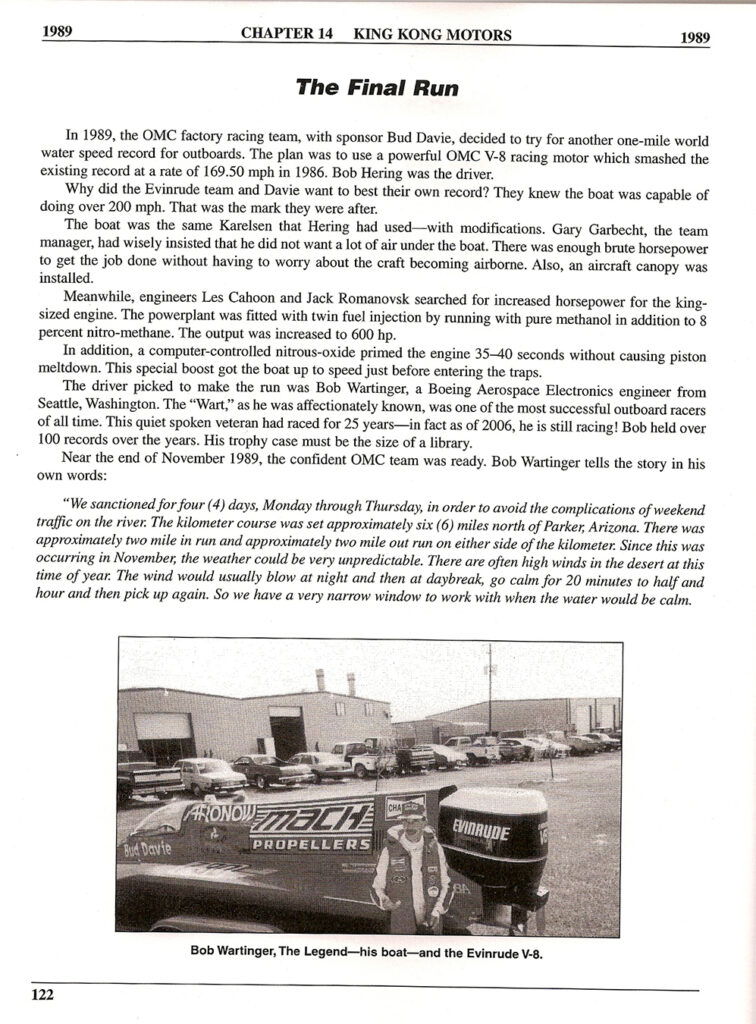

Davie subsequently called Wartinger. He wanted the boat to go 200 mph. “That’s what Garbrecht had talked him into, the goal was 200,” Wartinger says. “That was the plan, so we started testing during the fall, winter, and spring of 1987, ’88, into ’89. Then we went to Parker to watch the marathon race on Thanksgiving. We had four days sanctioned for the last week of November for the kilo straightaway. They hired officials, a helicopter, rescue people, the whole thing. Bedford was the owner, Garbrecht was doing the team managing and work. Bedford pretty much paid for everything, all the shop work, all the parts, all of the work on the boat.”

During the testing leading up to the record attempt, a number of changes were made to the boat. “We put a cockpit (capsule) in it,” Wartinger explains. “First cockpit in the United States, because it’s registered as number one with APBA. The builder was Matts D’Occa. We had to modify the cowling over the capsule three times. One was because of aerodynamics, others were just to get me to fit in there. We used different rudders. We built radiators. We ran a closed cooling system for a while. We did a lot of experimentation on the boat; shoes on the back, shoes off the back. We locked the engine at a slight angle because the engine weighs so much and had so much torque. We put an inboard-style rudder on the right-hand side, so steering was by rudder. We took the skeg off the lower unit.” Propellers were made by Garbrecht’s company, Mach Propellers.

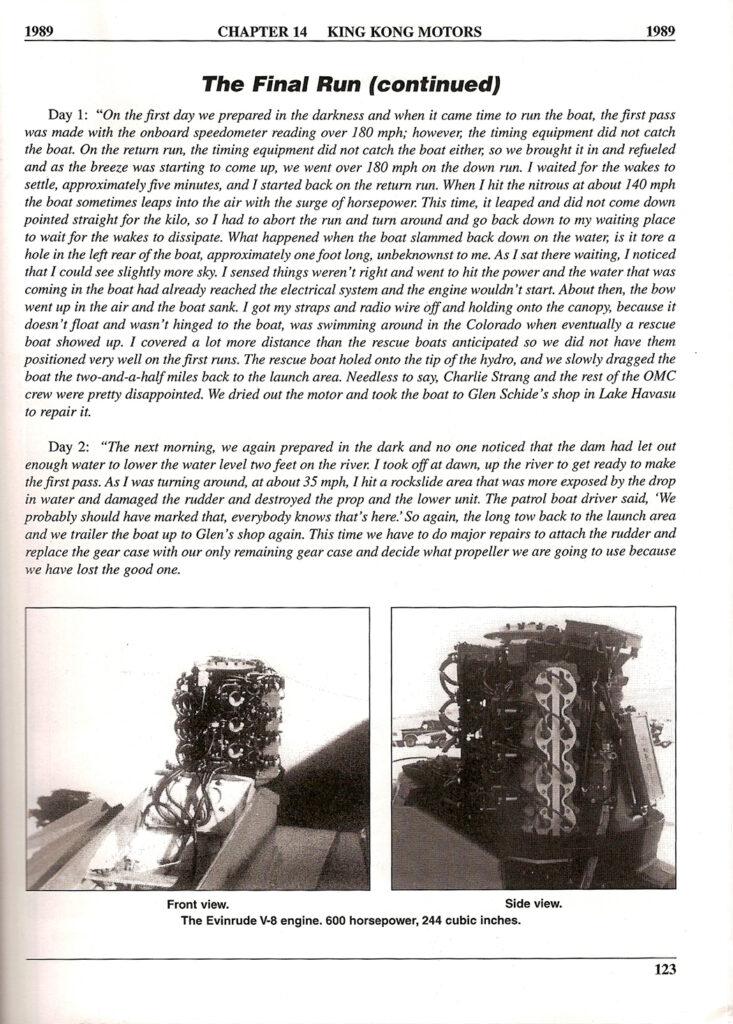

The engine was a 3.5 litre, two-stroke Evinrude, with alcohol fuel. A nitrous oxide system was added. “We added the nitrous system because there was a bit of a flat spot at 145 to 155 miles an hour,” Wartinger says. “They had a little bit too big of a prop, you’d use the nitrous to go through it. But it was a mild nitrous system. We could use the nitrous all the way through the run. So we had horsepower with alcohol plus nitrous.”

Wartinger describes the enclosed cockpit. It lacked things that are now standard equipment. For one thing, there was no air mask. “By today’s standards it would not have been a sufficient capsule, in many ways. I had a harness and all of that. The final canopy, we had a light aircraft builder make it, so I had good optics, polycarbonate, and I had great visibility from it. The right shape for aerodynamic reasons.”

Most of the pre-event testing took place at Lake Hamilton, Florida. “We tested the equivalent of two years, except for the summer,” Wartinger says. “There were wakes and things on the lake. Lake Hamilton is a good place to test in Florida. That’s where Second Effort’s headquarters were.”

Finally, the time for the run for the record arrived. It was the last week of November, 1989, at Parker, Arizona. The sanction was for four days. Ted May was the referee. Wartinger remembers the first three days as having their share of frustration and disappointment. “We went in the water at 5:00 in the morning,” he begins, when recalling the first day. “I went down through the traps, the boat ran 180 and they didn’t get it. The scanners missed it. I came back and the scanners missed it. Because we used so much fuel, I came in to re-fuel it. Go back out and do 180 down. On the way back, when I hit the nitrous, the boat jumped. Sometimes it took a hop with that power increase. Came down hard and wasn’t pointed straight. I took it back down because they’re starting about a mile from the traps for the end run. While it’s sitting there, when the boat had taken the hop, a piece of the bottom came off, on the left rear side. The bottom was only a quarter of an inch on that boat. I heard some gurgling and then I started seeing a bit more blue sky while I was sitting there. I hit the starter switch and it wouldn’t start because the battery was under water in the back. I just radioed, ‘We’re going down.’ We did not have a lid that was hinged to the boat. We were not sure it would float. I had to get all my stuff off and then hang on to the canopy and get out of the boat. Ice cold Colorado River in November. Got picked up and it was totally under water. They dragged it back. We took it to Glen Shaid’s shop. We put a piece on the bottom, dried out the engine, replaced the electronics, and put it all back together. So that was the end of the first day.”

The second day produced more problems. “We’re out there in the dark,” Wartinger remembers. “No one notices that the water behind Parker Dam had dropped a couple of feet. When I make the turnaround about a mile up the river before the traps, the rudder strikes a rock wash that was unmarked, and at 30 miles an hour it pulls the rudder loose from the back of the boat, wipes out the lower unit and the good propeller. Boat comes down on a tow rope again, but this time it’s not sinking. Some progress! We had to go back to Glen Schaid’s shop to reinforce the whole rear rudder bracket and put the other gear case in. We had only one other gear case. It’s putting a lot of power going through the gear case; we’d wear ‘em out. They had to be rebuilt quite often.”

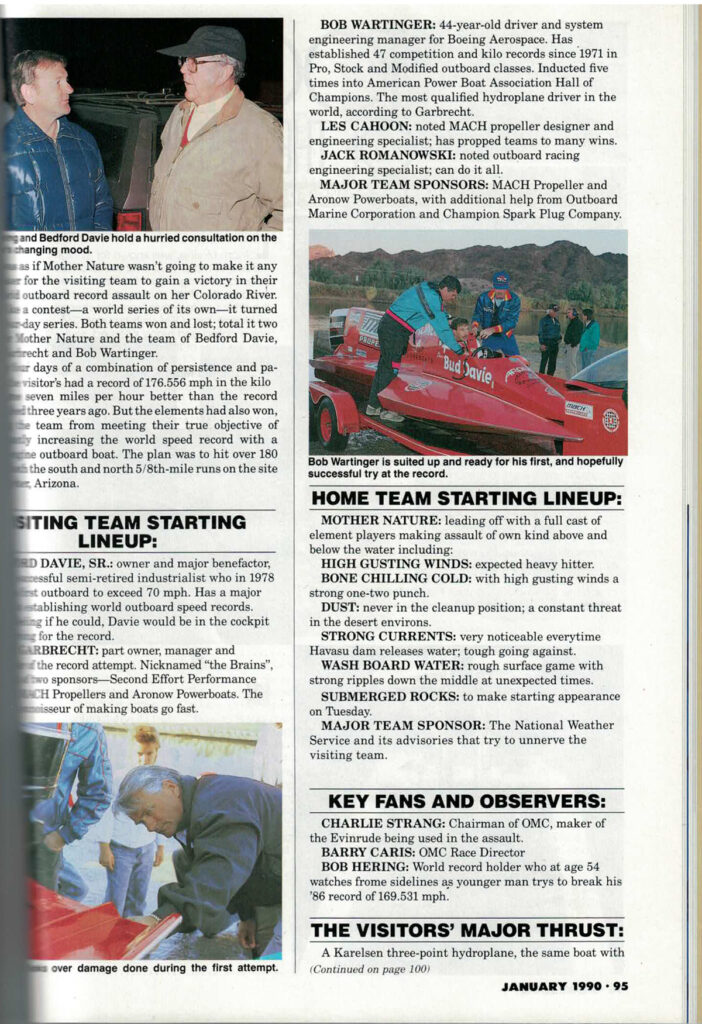

Part of the January 1990 POWERBOAT Magazine article about Bob’s frustrating but ultimately successful Parker record run.

The third day was used for testing and tweaking. “One of the challenges was, they picked November and the desert winds tend to blow,” Wartinger explains. “It’s at dawn that the wind switches direction or you get a bit of a calm from the night wind to the day wind. We had a window in there. We did not have all day, we just had this window of time. We changed propellers back and forth and we got up to 178. We were over the old record but did not want to advertise that because we still had a day left on the sanction. We wanted to tune the engine a little bit more. We made a number of runs on Wednesday.”

Thursday was the final day of the sanction, and the last opportunity to significantly raise the record. “Came out, went over 180 on the way down,” Wartinger says. “Then on the way back it felt like the engine was working hard but it wasn’t going anywhere. It ended up being about 170. I came in to get more fuel and when I hit the starter switch to go back out, it was locked up. The gear case had been heating up on the way back and that ice cold water, once I stopped, it was burned. So there we were, that was the record.” Wartinger’s first run was 181.569 mph and the return run was 171.544 mph, for a two-way average of 176.556. It was an amazing accomplishment for an outboard-powered boat. By comparison, when the Unlimited hydroplane Slo-mo-shun IV set the mile straightaway record with its V-12 Allison aircraft engine in 1950, its average speed was 160.3235 mph.

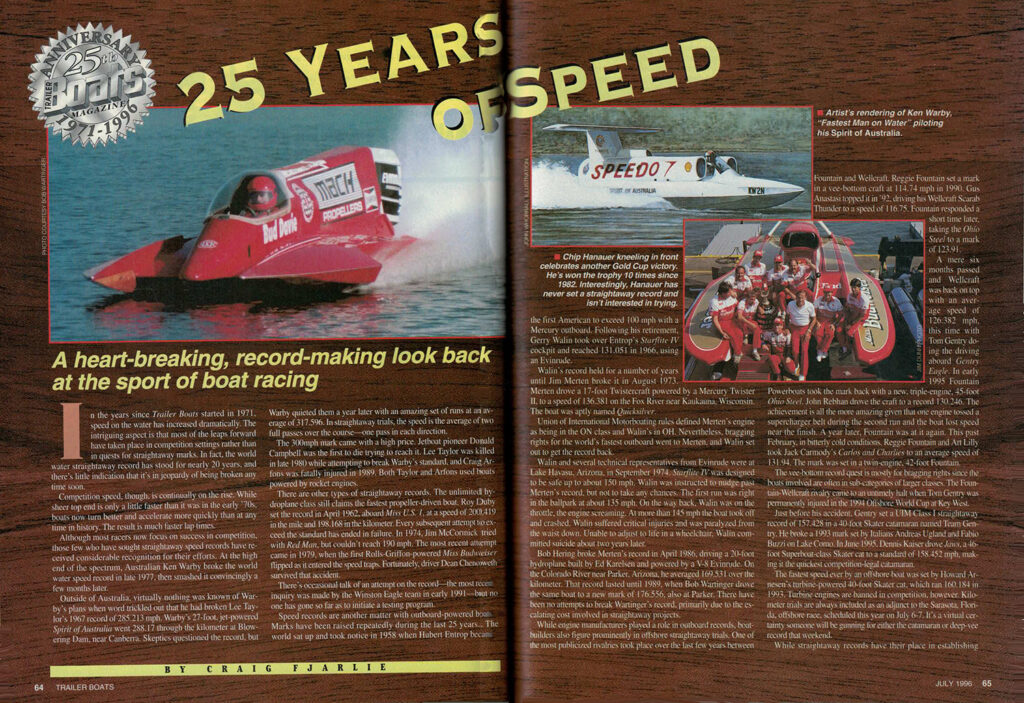

Craig Fjarlie’s article 25 YEARS of SPEED in the July 1996 issue of Trailer Boats Magazine highlights Bob Wartinger’s Parker record along with other record-setters.

Wartinger’s record still stands. He takes a philosophical look at speed marks. “You never really and truly own them. They’re like library books. You can borrow them and then somebody else borrows them, but you never own the book. When you have the record for a while, it’s like a library book, then somebody else has it. So, it’s just a process of who’s going to do it next.” When asked what it would take to break the record, Wartinger offers his opinion. “We looked at 200. I believe we just needed to design a boat that would be a little bit longer to do it.” The boat Wartinger drove was 20 feet in length. Before any additional development was begun, fate intervened. “Bedford passed away, and then Garbrecht passed away. They were kind of spearheading the project, so that’s where it…” his voice trails off.

There is more to the story of the boat, however. “The boat went back to Florida,” Wartinger begins. “Gary Garbrecht had been storing it, then it went to his son, Alan. He gave it to Race Rock Café in Orlando. It was a restaurant that showcased racing equipment. It was full of drag cars, sports cars, all kinds of racing vehicles. The boat was raised to the ceiling. It was painted white from its original red. It didn’t have an engine on it, just had an empty cowl and the lower unit. It was there for a number of years, and then Race Rock closed.” Previous owners of the racing equipment were notified they could retrieve the items they had donated. “Mike Jones was interested in it. He and Greg Jacobsen obtained the boat from Alan Garbrecht and had Duke Waldrop take it to Texas where it sat for about a year in storage,” Wartinger continues. The boat eventually was moved to the Lincoln City, Oregon shop operated by Craig Selvidge where it was refurbished. “They added a few decals, it has a beautiful red paint job on it now, and he inlaid the dash. It looks way better. Underneath, it’s still a flexible flier. After all these years you can pick up a sponson and the back would stay still, probably,” Wartinger says with a smile.

The boat is usually stored indoors at Jacobsen’s Marina in Lynnwood, Washington. When Ed Karelsen died on December 29, 2018, a memorial for him was held at the Hydroplane and Race Boat Museum in Kent, Washington. “Jacobsen brought the boat to the memorial,” Wartinger says. “That’s the only time it has been outside of the marina.”

Although the boat holds the record as the fastest outboard-powered craft through the measured kilometer, its days on the water are over. Wartinger, however, occasionally climbs into an outboard racing craft and pursues other records and awards. His list of accomplishments is long, and as far as he’s concerned, there is still more to do.

Above: keep driving, and someday you may earn one of these…

Below, the poem Open Water by Donald W. Peterson explains why people like Bob Wartinger keep doing what they do…

Featured Articles